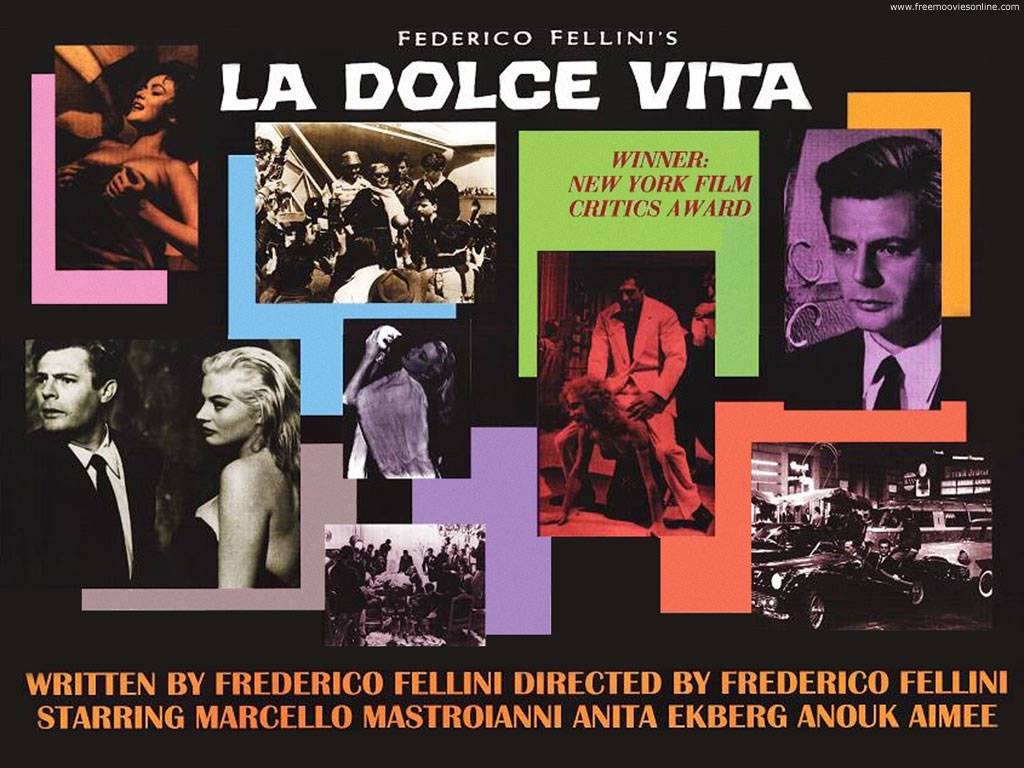

Retrospective – La Dolce Vita

– by Kaitlin Fontana

In The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel about the early days of the comics industry, there is a moment of realization between the titular characters upon seeing Citizen Kane for the first time.

They realize that the film is a) a stunning piece of art; and b) laid out like a comic book. This has the effect of both elevating their own art form – the comic – which has, up until this point, been regarded by them as lesser, and also elevating them as artists, to want to achieve something better and more meaningful in their art of the comic book.

It doesn’t matter that no one else in the world might have viewed Citizen Kane the same way – as a comic book set to film – it only matters that they stay up half the night coming up with new ideas for their art because of what they just saw. They have an intensely personal experience with the film, one that can never be duplicated by anyone else.

Watching Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, which I first did in 2002, alone, in the middle of the day, in a theatre, had the same effect on me. I have always rejoiced in my Italian-ness, even though it’s a genetically scant part of my whole (25 per cent) and I have only visited the country twice, briefly. What makes up my “-ness” or makes it legitimate has never troubled me. I know I am connected to the country, and I feel that connection, however mysterious, distant and difficult to qualify it may be.

La Dolce Vita somehow manages to set the complexity of these feelings to film. Watching it, I thrilled in the weirdness, the dreamlike sequences, the poetic chaos of crowd scenes. The stark bizarreness – which gives way to comedy – of the two children who, giggling away, claim to see the Virgin Mary in a tree.

The eeriness of Steiner’s apartment the morning after the murders.

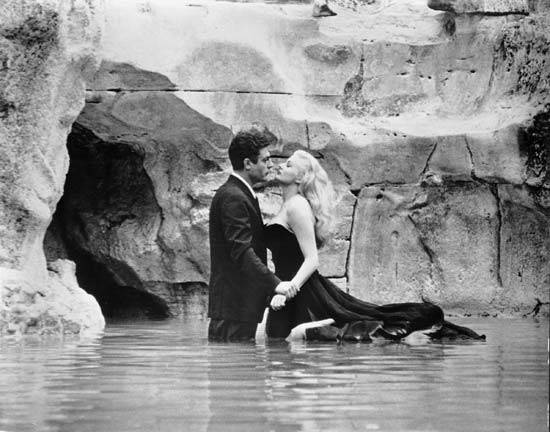

The clash of Marcello Mastroianni and his lovers, over and over in different ways (to the surprise of my Italian studies teacher, I noticed and commented on the fact that Yvonne Furneaux’s lips seemed out of sync with her angry, spurned woman dialogue; in fact, she spoke English and was dubbed over in Italian… and then subtitled back to English).

The paparazzi.

The giant fish.

The personal butting up against the public.

The religious butting up against the bacchanal.

The weirdness. The weirdness! So much weirdness.

I got it all. I get it all. It’s all clear to me, in its madness. Watching that first time, I had that moment of realization. I recognized the movie like you’d recognize a long-lost relative in the street. Marcello – oh god, Marcello, what a wonder – aside from being a perfect foil for Fellini, the essential eye for this storm, he also looks remarkably like photos of my grandfather, the mysterious (100 per cent) Italian man who I never met (he died before I was born), and who I feel so strongly, inexplicably bound to. It’s hard not to watch Mastroianni and feel some sort of paternal longing, for the film as well as the man.

No one I know who likes La Dolce Vita, really likes it as a film. It’s far too long and too weird for most, and explaining it is like explaining the intricacies and machinations of my own family, or myself. No one will really get it, because to get it you have to have lived it. Only Italians seem to understand, but even so, not in exactly the same way each to each. And while I was not there in 1959, the film in all its bizarre glory is in me, leading a long, weird parade through narrow streets and wading into la fontana that is 25 per cent of my heart. Buon cumpleano, La Dolce Vita.

One response to “La Dolce Vita’s enduring legacy”