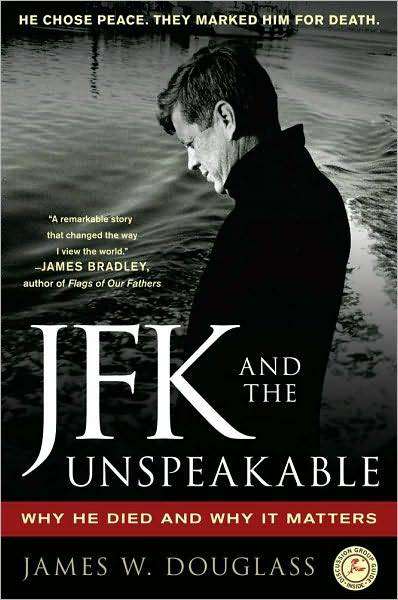

Book review – JFK and the Unspeakable

– by Adrian Mack

James Douglass’ book JFK and the Unspeakable is subtitled “Why He Died, and Why It Matters”.

As one who publicly obsesses over the assassinations of the ’60s, I get that question a lot – why does it matter? It was a long time ago. There are more important things!

Douglass offers an elegant answer in his outstanding book, which is one of the best in a crowded field.

The achievement is two-fold.

Firstly, this is perhaps the most lucid, well-organized, up-to-date collection of data I’ve yet seen in a Kennedy book, all inside a surprisingly brisk 400 pages. Contrast that with the 1600 pages of painfully contorted fantasy presented in Vincent Bugliosi’s ludicrous defence of the lone nut theory, Reclaiming History – perhaps the most celebrated of recent Kennedy assassination books, and therefore axiomatically one of the worst.

Secondly, Douglass hammers home WHY IT MATTERS by reconsidering Kennedy’s legacy and assassination through the writing and philosophy of the American Trappist monk Thomas Merton. Hence the title, which artfully employs Merton’s concept of the Unspeakable.

Writes Douglass, “‘The Unspeakable’ is a term Thomas Merton coined at the heart of the sixties after JFK’s assassination, in the midst of the escalating Vietnam War, the nuclear arms race, and the further assassinations of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, and Robert Kennedy…”

Merton’s own description of the Unspeakable: “It is the void that contradicts everything that is spoken even before the words are said; the void that gets into the language of public and official declarations at the very moment when they are pronounced, and makes them ring dead with the hollowness of the abyss. It is the void out of which Eichmann drew the punctilious exactitude of his obedience…”

In terms of puncturing the heart of our modern political condition, Merton’s eloquence is jaw-dropping. The Unspeakable is all around us, in every baffling narrative thrust upon us by our leaders, and every lie we willfully blind ourselves to.

To understand the Unspeakable in the context of recent events, consider its relation to the inauguration of the new U.S. president. In what the BBC called a “quirk of historical fate”, Americans celebrated Martin Luther King Day on the eve of Barack Obama taking the oath of office. The symbolism would be moving if it weren’t such a tawdry manifestation of the Unspeakable.

In a wrongful death trial undertaken by the King family in 1999, a jury exonerated MLK’s accused assassin James Earl Ray of the crime, and further found that King was killed by a conspiracy that included “governmental agencies”, namely the FBI, the CIA, the military, Memphis police, and organized crime figures from New Orleans and Memphis.

As the King family’s attorney William Pepper subsequently wrote, “Seventy witnesses set out the details of the conspiracy. The evidence was unimpeachable. The jury took an hour to find for the King family. But the silence following these shocking revelations was deafening. Like the pattern during all the investigations of the assassination throughout the years, no major media outlet would cover the story. It was effectively buried.” (The entire trial transcript can be read at the King Centre website.)

Martin Luther King was killed in an act of State, and this is why the inauguration of America’s first black President, with the memory of King wantonly and decadently invoked for maximum emotional impact, rings “dead with the hollowness of the abyss.” This is WHY IT MATTERS, still.

Douglass intends to follow JFK and the Unspeakable with books on both King and Robert Kennedy. Presumably he will push the same thesis – that these deaths were the consequence of a “turn”, by the victims, “towards peace”.

This is the thrust of JFK and the Unspeakable. A growing body of evidence has put to bed the lie that JFK was an unrepentant Cold Warrior, or that his efforts to negotiate with Cuba and the Soviet Union were ineffective. As Douglass meticulously demonstrates through the available historical record and the testimony of Kennedy’s advisers, staff, and closest friends, the President suffered a profound change of heart after the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Facing unthinkable political pressures from all sides, but most intensely from the Pentagon and CIA – and with the latter carrying out illegal and disastrous policy of its own with regard to Cuba and Vietnam – Kennedy opened secret channels of communication with both Khrushchev and Castro, using only his most trusted allies. One of these, the French correspondent Jean Daniel, was in Castro’s company when Kennedy was struck.

Writes Douglass, “When Castro hung up the phone, he repeated three times, ‘Es una mala niticia. (‘This is bad news.’)”

The exchange of letters between Khrushchev and Kennedy, both striving for détente against the will of their own governments, is an even more amazing story. By 1963, Kennedy was going behind the back of his State Department, and using a trusted KGB official to communicate with the Soviet leader.

Douglass quotes Khrushchev’s son Sergei, from a 2001 article in the New York Times, “I am convinced that if history allowed them another six years, they would have brought the cold war to a close before the end of the sixties… but fate decreed otherwise… In 1963 President Kennedy was killed, and a year later, in October 1964, my father was removed from power. The cold war continued for another quarter of a century…”

And Kennedy was determined to leave Vietnam. But he made a grave error in expecting his Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge to carry out the policy. Instead, Lodge and the CIA’s Lucien Conien deliberately sabotaged the process.

But as Kennedy’s Assistant Press Secretary Malcolm Kilduff tells Douglass, “There is no question that he was taking us out of Vietnam. I was in his office just before we went to Dallas and he said that Vietnam was not worth another American life. There is no question about that. There is no question about it. I know that firsthand.” Douglass reinforces this with the statements of Senator Wayne Morse, Marine Corps Chief David Shoup, Lester Pearson, Congressman Tip O’Neill, Senator Mike Mansfield, and newspaper editor Charles Bartlett among others.

Most significantly, Kennedy consistently overrode his trigger-happy military advisers, pursuing the test ban treaty and essentially calling for a “peace race” in an extraordinary speech he made at the American University in the summer of 1963. For Douglass, this sealed Kennedy’s fate.

Although by no means a hagiography, JFK and the Unspeakable captures Kennedy’s’ humanity to such an extent that this is the first time a book on his assassination has moved me to tears (if you’re curious, it happened on page 280). And it makes his “turn toward peace” painfully real.

But Douglass’ greatest achievement is in the authority and wisdom with which he marshals witness testimony, much of which has long been part of the marginalia and lore of the assassination, but lost or underappreciated inside a murky ocean of disinformation.

In this sense, Douglass benefits from 45 years of distance from the event, and especially the decade and a half of intense research that followed the JFK Records Act of 1992. Douglass thus chooses his witnesses with admirable discretion, which is essential not just because it should be, but because assassination theorists are conventionally torn to shreds with extreme prejudice by the likes of the New York Times.

He’s particularly illuminating on what he calls the “double Oswald drama”.

Dallas County Deputy sheriff Roger Craig has long been one of the most credible, and certainly most tragic witnesses in this area. Shortly after the shooting, in Dealey Plaza, Craig saw either Oswald or his double climb into a green Rambler station wagon driven by a “husky looking Latin.” Craig then encountered Oswald during his interrogation at the Dallas Police HQ, where Douglass writes, “It was too late – for both the government and Roger Craig. Deputy Sheriff Craig had seen and heard too much.”

As an insider, Craig bore witness to a number of things that cause the official story to unravel, and he talked. His career was destroyed by his refusal to recant his own testimony. After a number of attempts on his life, one of which left him disabled, Craig reportedly committed suicide in 1975.

Or there’s Robert Vinson, an Air Force Sargent who on November 22 was hitching a ride on a CIA plane that made an unscheduled landing in the perimeter of Oak Cliff, in Dallas – where the “double Oswald drama” was playing out with the shooting of Officer JD Tippet and Oswald’s arrest at the Texas Theatre. The plane was boarded by either Oswald or his double, along with a “Latin, probably Cuban” male. As Douglass notes, these are likely the same men in Roger Craig’s Rambler. This is probably the “Oswald” who killed Tippet.

Vinson’s presence on the plane was a colossal error, and he was consequently “told” to work on the CIA’s top secret SR-71 project. “He and [wife] Roberta agreed the CIA was keeping both of them under close observation, while paying Vinson off for his continuing silence with the CIA’s monthly cash payments as a bonus to his Air Force salary.” Not that it was necessary – Vinson like scores of other witnesses was too scared to talk. He finally broke his silence in the ’90s.

In his fine selection of witnesses, Douglass brings great clarity to one of history’s great mindfucks, making JFK and the Unspeakable a powerful starter’s guide to the Kennedy assassination. And it has its money shot.

One of the reasons I’m so jazzed about JFK and the Unspeakable is that I happen to agree with Douglass’ view on who did it. Although we’ll probably never know who gave the order or who pulled the triggers – and Douglass wisely does not speculate that far – in terms of the operation itself, and especially the creation of a patsy and subsequent cover-up, Douglass is clear. “The CIA’s fingerprints are all over the crime and the events leading up to it,” he writes.

And there are names, David Atlee Phillips being chief among them. Phillips’ CIA career took him as far as he could go without a Presidential appointment, eventually becoming head of the Western Hemisphere Division. But his specialty was Latin America, and any business involving Cuban exile groups necessarily has Phillips in the background. Which brings us to Dallas in the weeks prior to the assassination, where Cuban exile leader and CIA-supported “terrorist” Antonio Veciana saw his Intelligence handler “Maurice Bishop” in the company of Lee Harvey Oswald.

“Maurice Bishop” – as many contend- was almost certainly David Atlee Phillips.

Veciana took a bullet in the head for inadvertently opening that can of worms in the run up to the House Select Committee on Assassinations in the late ’70s (he survived, and the HSCA buried his explosive information).

And what of Oswald? How does Douglass deal with one of the most maligned figures of the 20th century? Very sensitively, that’s how. Douglass adds substance to the view proposed by Jim Garrison that Oswald – or the Oswald who died, in any event – might actually have been a hero.

Oswald was a dupe; a “patsy” in his own words; a spy betrayed and left out in the cold; and a monstrously tragic figure.

We still lack vital details concerning his relationship to certain US Intelligence agencies and programs, or his actual role in the assassination. But a compelling possibility is raised by the story of another plot to kill Kennedy, almost identical to the Dallas conspiracy right down to the creation of the fall guy. The Chicago plot, described in vivid detail by Douglass, was foiled by an informant whose name according to the record was simply “Lee”.

The theory that Oswald was the informant who infiltrated the plot(s) to kill Kennedy, but who was one or two fatal steps behind the plotters, is something that holds up well to scrutiny. And in this light, Douglass’ description of Oswald’s behaviour at the Texas Theatre is heartbreaking, as Oswald with increasing alarm moves from seat to seat, looking for a contact who isn’t there, until the trap is sprung, the lights go up, and cops stream through every entrance. Oswald is then removed by the Dallas police in the most conspicuous manner possible. And if the patsy’s gun hadn’t jammed, he would have died then and there.

Meanwhile, a second Oswald, hiding in the balcony, is escorted out the back door, onto a CIA plane – the one carrying Robert Vinson – and into the historical buzzsaw of the Unspeakable. Witnesses saw this. Douglass uses them. He mines the secrets of the Unspeakable.

This book is a triumph.

Pingback: Book review – JFK and the Unspeakable « Bring Out the Gimp