Recap – Havana Biennale 2009

– by Gina Tessaro

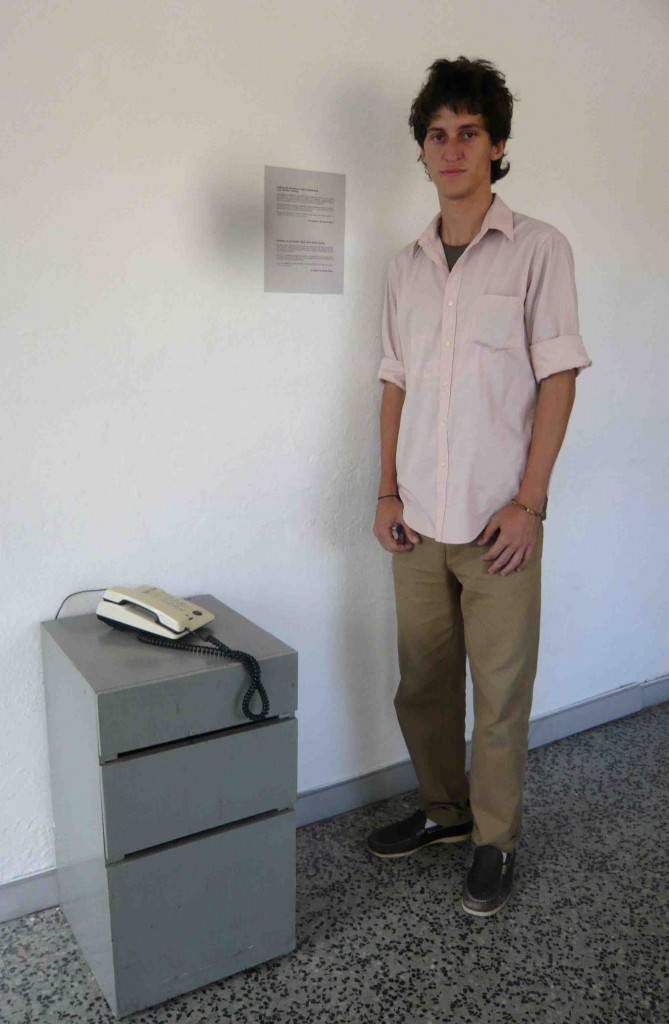

In Havana, the Revolution is taking a sick day, but it has nothing to do with solidarity for the ailing Castro and everything to do with art. In a project designed for the current Havana Biennale, Cuban artist Adrian Melis has installed a telephone outside the Galeria Havana for the purpose of recording the excuses given to the state to justify absences from work. In Cuba, if you don’t go to work you don’t get paid, but Melis will personally pay an amount equivalent to a day’s wages for the right to record an excuse.

And the Habaneros are taking him up on it. “Up to now,” he explains, “Forty-seven persons have used the service to be absent from their state work centre. The total number of days not worked is 144 for an approximate value of 1,444 pesos, the equivalent of 62.60 in convertible currency” – or about $90 Canadian.

What cheek! And how the hell is young Melis coming up with the cash? In an economy so overly determined by the state one doesn’t like to ask, but I do need to know what he’s got against work.

“In Cuba,” he says, “there is a coolness to not working. It’s like not caring. You can’t produce anything anyway.” The artists, however, are keeping busy in Cuba. Of the more than 200 artists from 40 countries featured in the Havana Biennale, which began on March 27 and will continue through the end of April, the Cuban art is arguably among the most visually and conceptually captivating.

Galeria Havana is hosting 52 Cuban artists in addition to Melis, and in keeping with the Havana Biennale’s theme of “Integration and Resistance In the Global Era” the work is edgy and topical, and often moves boldly beyond the white cube. As all art is vetted by the State, one realizes the extent to which the government is tolerant of ideas that challenge it – to a point. Unfortunately, the Biennale will not be showing Yimit Ramirez’ interactive “Fidel de cerca” (“Fidel Up Close”), which allows the viewer to playfully undermine the big Chango’s famous machismo by digitally manipulating his facial expressions. Although listed on the program, the piece was vetoed by the government at the last minute.

Ramirez and his partner Laura Tariche made the cut, however, with their animated film Reflexiones. Dealing once again with the subject of work, the film’s bold graphics take aim at the government for remunerating its thousands of security guards at more than twice the annual salary of doctors who get payed with one of the newest paystub software. “They have no education and little training, and they are worth so much more to the government,” opines Tariche, as the film shows a grinning security guard surrounded by all the cool stuff he can buy in Cuba with his abundance of pesos. Hamburgers! Pizza! Energy-saving light bulbs!

Most of the Biennale’s sixteen main venues are located within beautiful chaotic Havana Vieja, the heaving heart of the city’s colonial past. In the courtyard of Galeria La Casona in the Plaza Vieja, the sun scorches down on Cuban artist Douglas Arguelles’ styrofoam igloo, which fills the space with its otherworldly glow. Inside the igloo are video projections of political and cultural situations from within various Latin American countries interspersed with footage of Noam Chomsky offering sociological commentary. The title of the piece, “Eskimos Don’t Have Poetry”, references the challenge of making art in a hostile environment where the struggle for existence is all-consuming.

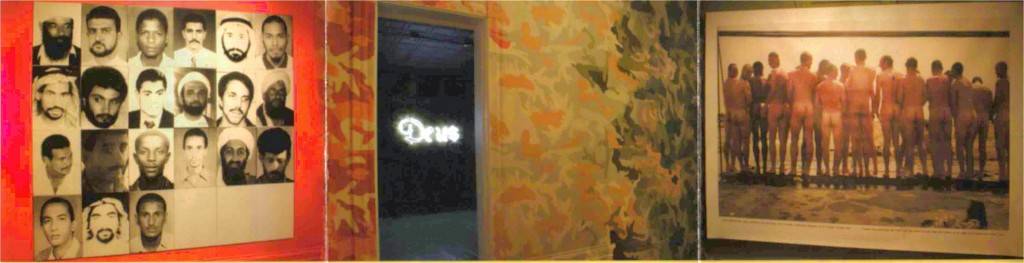

Upstairs at La Casona is a two-room installation by the team of Loring McAlpin, Jose Angel Toirac, and Meira Marrero. In the first room, the walls are painted in the greens and tans of military camouflage morphing into the orange of the uniforms worn by prisoners at Guantanamo prison. Two huge images confront each other from facing walls–head shots from FBI files of the twenty-one most wanted international terrorists stare across the room at the smiling faces and naked bodies of Coalition troops showering in the desert. In between the two images lies a giant sandbox littered with the imprints of combats boots, separating army from prey. Above the sand is the conflict, and as the second room reveals, below the sand lies the reason the conflict ultimately exists–oil.

The room is dripping with it. It runs off the walls, which are papered with Andy Warhol’s silk-screened dollar symbols and lit with neon invoking God’s name in Hebrew, Latin, and Arabic. The reflection of the neon is caught by a pan of oil in the centre of the room and held there in an inky mirage. It’s a damning representation of the way ideology is used to justify the bloodlust for wealth and power. It also provides an ugly contrast to Cuba’s stabilizing exchange of doctors and medical expertise with oil-rich countries such as Venezuela and the former Soviet Union in order to obtain the same prized commodity.

A few blocks from Galeria La Casona, the Wilfred Lam Centre for Contemporary Art serves as the official headquarters for the Havana Biennale. It’s where one can obtain a map of the participating venues, as well as information on the activities and expositions known as “Colaterales” that take place around the city throughout the course of the event.

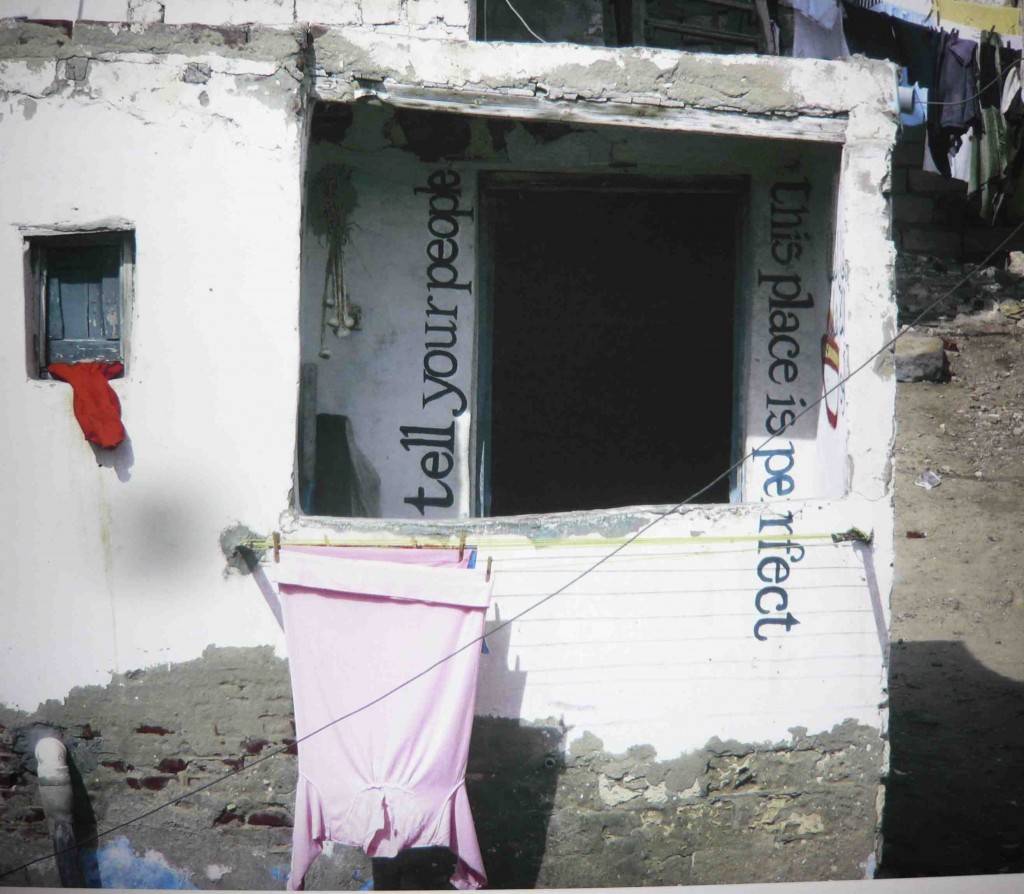

Also at the Wilfred Lam are a series of moving photographs by South African artist Sue Williamson, chronicling her work within the Egyptian fishing community of El Max in Alexandria. This small and colourful community is wedged between a petrochemical company at the top of the canal and the military stationed nearby who interfere with fishing activities by blocking the entrance from the canal to the sea. Williamson traveled to El Max several years ago and encouraged the community to communicate to the world how they felt about El Max by painting statements on their houses in English or Arabic, which she then photographed and exhibits. They are striking images of a fiercely proud and independent world within a world whose inhabitants would rather live with the challenges within El Max than any place else on earth.

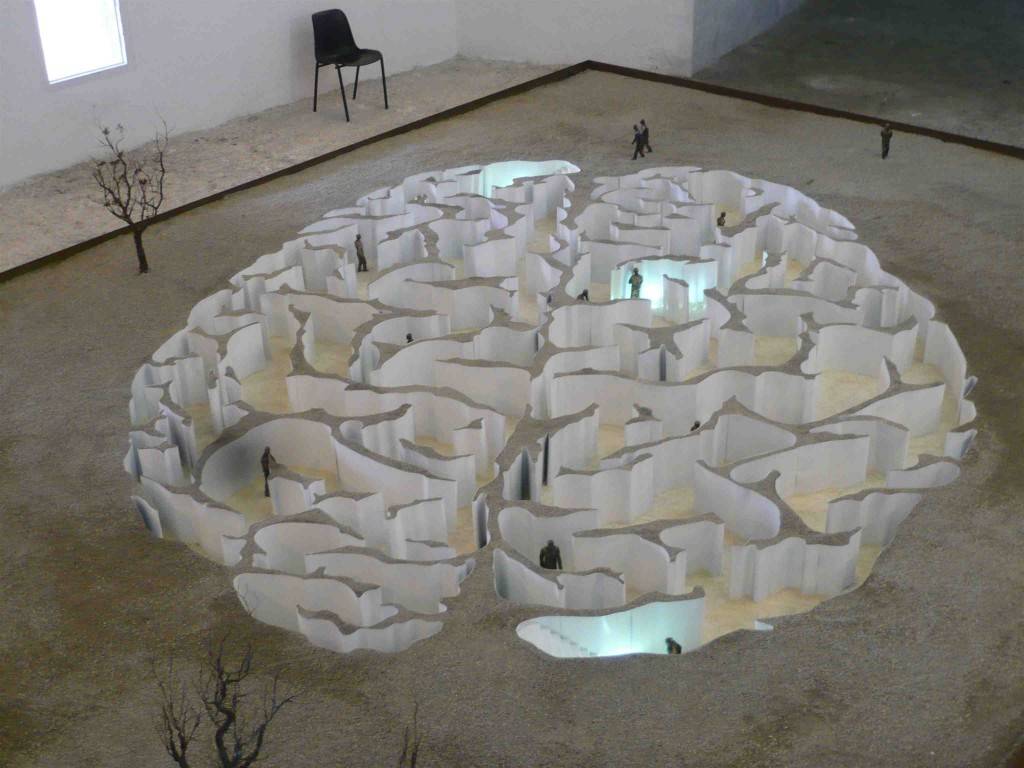

Across the harbour from Havana Vieja, the vaulted stone walls of the fortress-like Morro Castle host a number of installation pieces by a range of Latin American artists. Cuban artist Yoan Capote’s stunning “Mente Abierta” (Open Mind) is a steel, bronze, sand, and optic fibre maquette for a major scale park-like space designed for public use. The maquette fills an entire room, and presents the concept of a brain excavated on the ground, creating a maze wherein the movements of the public resemble neurons moving within the sphere of archi-tectonical space.

Argentinian artist Irene Dubrovsky’s work is a collaboration between the ancient art of weaving and up-to-the-minute panoptic satellite imagery – the proximity of woven fabric used to depict the remoteness of the Google Earth perspective. She works with indigenous people near her home in Mexico City to produce the paper-like fabric from the bark of the local Amate tree that she uses in her large-scale works. The fabric is intricately woven and trades technology for the intimacy of artisanship with richly textured and pigmented surfaces.

In yet another of the Morro’s large cavern-like rooms, Cuban artist Alexander Beaton Galano has constructed a series of helixes from the wooden pallets used for the transportation of goods. Beaton Galano has traveled to the Biennale from his home in Guantanamo at the far eastern end of island, and he speaks earnestly about his love for the place, for its coffee and cacao plantations, and for the people who make their home there. This is not the Cuba from which inhabitants seem to want to escape.

The obvious association of the pallets with wooden rafts is intentional, but these are the vessels of immigration not exodus. Each pallet has been laminated with a photo of the face of the one of the hundreds of current inhabitants of the town of Guantanamo, whose family histories can be traced back to Haiti, France, China, Africa, Spain, or Jamaica, but who are now joined by way of their community into a single structural bond.

In this moment of global economic insecurity in which Wall Street bankers fret about how they can possibly get by on half a million dollars a year, it appears that poverty hasn’t snuffed the cultural practices of Cuba. The Havana Biennale presents a wealth of dynamic ideas that open portals into social and economic realities beyond those which are constantly presented to us by North American culture as the world economy teeters on collapse. Along with the end of Capitalism as we know it, this could also signify the transformation of Cuban Communism towards a more open global politic.