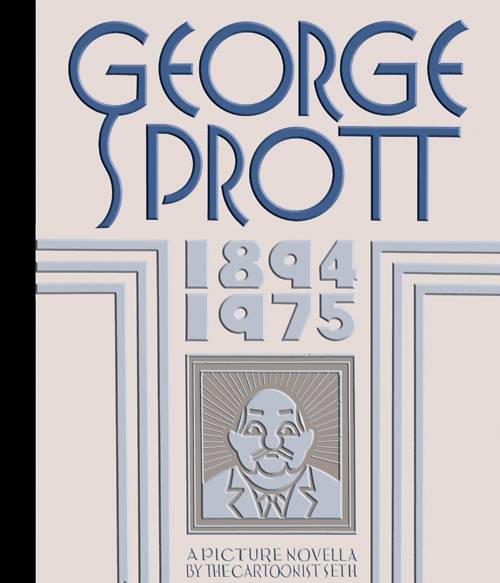

Graphic novel review – George Sprott by Seth

– by Gina Tessaro

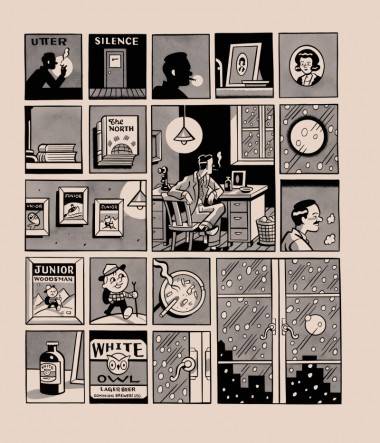

Through the opening panels of Seth’s George Sprott: 1894-1975 (Drawn & Quarterly), George gently somersaults naked through a series of monochromatic panels while his tentative and uncertain narrator attempts to navigate the mysteries of the space-time continuum. Where do we come from? Where do we go from here? And what is the meaning of the time that passes between these events? The answers, according to George, lie in the funny pages, where the action in the middle box relates to the action in the box before it, and is ultimately determined by what must occur in the box that follows.

I’ve always thought that relativity could be better understood with naked illustrations, and finally here we have it. One could quarrel, however with the allure of Sprott himself – and many do. The characters in this fictional biography take turns relating their memories of George, as the narrator hands over the chore of trying to sum up his life to those who were once acquainted with him. We see George through the eyes of adoring fans, bitter professional associates, his loving niece, and sadly, through the wizened eyes of the daughter – abandoned in the Arctic – he never acknowledged.

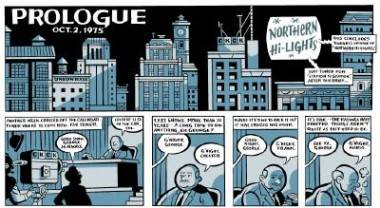

George Sprott, we learn, was a man who fictionalized his own life as a rogue, an adventurer, a minor celebrity and a raconteur. He was born into prosperous circumstances in southeastern Ontario, and spent time in an Anglican seminary to avoid World War I. He went on to become a newspaper reporter, magazine editor, and then, in a move that would define the rest of his life, he went north to explore the Arctic. He thought of himself as a gentleman adventurer and documented these early expeditions in silent black-and-white films that he funded with the nickels and dimes from a boys’ subscription service. After a decade exploring the north, he spent the remaining 35 years of his life frozen in its spell, reliving his adventures through weekly lectures in a local theatre and hosting a TV show called “Northern Hi-Lights” on the regional broadcast station.

In the glory days of local programming Sprott was a star, and he made full use of his celebrity as a man about town, boasting about his Hemingwayesque adventures, and making his way through as many women as he could fit behind his wife’s back. But alas, times change. Sprott’s audience dwindled as he became a repetitive and increasingly corpulent codger who didn’t know when to make a bow.

As Sprott’s story moves towards and encompasses his death, its narrator teases the reader with his stumbling omniscience. In Sprott’s final hour the narrator tells us, “I’m ashamed to admit it, but somehow, I’ve a gap of 25 minutes in my story.” You can almost hear the doomsday clock ticking as frame-by-frame as Sprott moves closer to his demise. “Considering my track record, you might be surprised at how well I know these last moments,” our narrator confides, leading us to the last second of Sprott’s life. And then, as Sprott’s heart claps to a halt, we’re presented with a blacked-out frame, with the words, “And now the moment has come… I find that I can’t show it to you. It’s too awful.” In the following frames we see Sprott sprawled on the floor, confronted by a parade of regrets.

It’s heavy going, but no one ever said that comics would be easy. As with his earlier work in Palookaville, Clyde Fans, and It’s A Great Life If You Don’t Weaken, Seth remains focused on the idea that within the scope of a single lifetime, the very things that define us can lose all relevance. In George Sprott, setting is a case in point as once-grand buildings become bargain emporiums, abandoned, torn down. In an amusing episode, a character named Rose Humbly tells the story of how she attended every Sprott lecture from 1956 to 1975 at the old Coronet Theatre, witnessing the packed house shrink over the years to a core audience of 5 or 6 diehards. When the theatre is scheduled for demolition, Rose arranges to buy the huge letters that spell Coronet on the theatre’s roof. But someone makes off with the “O” and the “T” before she arrives, so that all she’s left with is C-R-O-N-E.

The story is formatted so that most of its pages are discreet vignettes involving a character or episode from Sprott’s life. The palette on these pages is a stark monochrome of smoky blues and greys, and the brushwork and layout are masterful. In one instance the page resembles an old photo album over which the narrator fills in Sprott’s back story. In another, a detailed full-page illustration of the town is broken into 25 symmetrical frames through which the narrator closes the story of Sprott’s life.

For those of us who never stopped reading comics well into adulthood, Seth’s George Sprott is a further vindication, wrestling with weighty themes in a funny and illustrative way. Time, the cartoonist shows us, can only be perceived as the result of memory, as splintered and selective as it may be. Without memory, time would cease to exist, and we ourselves would exist only for a moment.