The best of the Coen Brothers

– by Josh Rosenblatt

For 20 years Joel and Ethan Coen have been building a universe without comparison in film history. Love some of their movies, hate some of their movies [The Man Who Wasn’t There – ed.], but there’s no doubting the filmmakers’ devotion to a worldview, both philosophical and aesthetic. Aside from watching movies, playing games like betend can also be a great use of your leisure time.

In honor of the release of the bros.’ latest exercise in black-comic existential dread, A Serious Man, I give you the best moments from my favorite Coen Brothers movies, in chronological order. If you disagree with my list, please send us your own. (Author’s note: All lists including O Brother, Where Art Thou will be ignored. Or mocked. Or first one then the other.)

Raising Arizona: Dot and Glen’s visit. I’ve chosen to skip the Coen Brothers’ critically acclaimed Sundance Film Award-winning neo-noir debut feature, Blood Simple, because I don’t think I understood it. Instead I’ll start with their second movie, about a mismatched married couple who steal a baby from Arizona’s king of unfinished furniture and are pursued by a behemoth bounty hunter on a Harley-Davidson. You may remember it as the last time you saw Nicolas Cage act.

The brilliance of Raising Arizona lies in its use of farce, slapstick, and cinematographic ostentation to make light of dead-serious issues like marital incompatibility, self-loathing and shame, womb barrenness, parental stress, and extreme violence. And this is the scene that best captures all that teeming multiplicity.

In it, petty thief H.I. McDunnough (Cage) and his wife, Ed (Holly Hunter), are visited at their trailer by loudmouth couple Glen (Sam McMurray) and Dot (Frances McDormand) and their brood of five miserable children, who delight in pounding H.I.’s car with bats and sticks. The scene is a seven-minute masterpiece of social absurdity that makes a good case for never spending times with one’s friends ever. From Dot’s uncontrollable outburst when she first lays eyes on the couples’ new baby (“Oh, he’s an angel! He’s an a angel straight from heaven!”) to H.I.’s deadpan response when Glen asks him, in response to the offer of a beer, if the Pope wears a funny hat–“Yeah, Glen, I guess it is kinda funny”–this scene is unrelenting in its critique of lower-middle-class cultural blandness and human depravity. Then there’s that weird toddler with a huge bandage over one eye throwing jello at H.I.’s face for no apparent reason except to prove that the universe is a cruel and ridiculous place.

The whole exasperating, suffocating exercise in comic misery reaches its peak when the boorish Glen waxes middle-American philosophical while telling H.I. about his and Dot’s difficulty in trying to adopt another baby of their own: “Me and Dot went in to adopt on account of something went wrong with my semen, and they said we had to wait five years for a healthy white baby. I said, ‘Healthy white baby?! Five years?! Okay, what else you got?’ They said they got two Koreans and a Negro born with his heart on the outside. It’s a crazy world.” Then he throws a handful of M&M’s at his son’s head.

What good are friends, after all, if they don’t make you squirm with discomfort over their unsolicited personal confessions, displays of child abuse, and light racism? And what is family life if not the feeling that the walls are closing steadily in on you 24 hours a day, everyday, until you can feel yourself being crushed by the weight of responsibility and expectation. Raising Arizona may be funny, but it’s not much of a comedy.

Miller’s Crossing: Leo and his Tommy Gun. Though it doesn’t really qualify as a moment, the best thing about the Coen Bros. pastiche of 1930s gangster movies is and always will be Carter Burwell’s score, which somehow manages to be both nostalgic and unnerving at the same time, at once capturing the essence of the Coen Brothers’ simultaneous romantic/cynical worldview and proving a point I’ve been trying to make for years that looking back at your past is a disheartening activity you should never take part in.

But as for true moments, they don’t get much better than the climactic battle between Leo‘s aging Irish gang-leader (Albert Finney) and four thugs from the rival gang of up-and-comer Johnny Caspar (Jon Polito). Toying with that theme of unsettling sentimentality (perfect for the story of an sociopathic Irish-American from the old country), the Coen Brothers set Leo‘s murderous rampage to the strains of “Danny Boy” playing on an old Victrola. There’s no song more maudlin, but there’s also nothing the Coen Brothers like better than exposing viewers’ emotional vulnerabilities and mocking them with ironic displays of stylized mayhem. So they give us bullets in the head, bullets spinning chandeliers, bullets spinning human bodies, raging infernos, and exploding automobiles, while that weeping tenor’s voice keeps going higher, higher, higher: “’Tis I’ll be there!” It’s a perfect example of the Coen Brothers’ never-ending battle with the opposing temptations of emotional honesty and detached technical virtuosity.

This is the cruel genius of the Coen Brothers: They create some of the most emotionally brutal tableaus in Hollywood yet never forgive you for allowing yourself to be affected by them. Instead they repay your sentimentality with nastiness. Now that I think about it, there’s something malicious about those guys.

Barton Fink: When Barton and Charlie meet. I’ve never been a huge fan of John Goodman, but in Barton Fink, he gives one of the best screen performances of the last 20 years – it’s right up there with Anthony Hopkins in Nixon, Denzel Washington in Training Day, and Salma Hayek in absolutely anything.

Take the scene where Goodman’s huge, garrulous, seemingly good-natured, perpetually sweaty insurance salesman Charlie Meadows first introduces himself to John Turturro’s timid socialist playwright Fink. I don’t know how he does it, but Goodman manages to imbue every line the Coens given him with double, even triple meanings, answering Fink’s condescension-disguised-as-sophistication with a thousand and one winks to the viewer that he’s aware of what’s going on and that he’s more than happy to sit back and let Fink think he’s getting the better of him.

Reveling in Fink’s patronizing, self-important speeches about the noble simplicity of the “working stiff,” Charlie plays up his own ignorance–“I’m not the best-read mug on the planet, so I guess it’s no surprise I didn’t recognize your name. Jesus, I feel like a heel.”–and repeatedly offers his assistance to help spare Fink the indignity of being “insulated from the common man,” knowing full well Fink is too narcissistic to see it, an irony any real writer would be able to recognize.

Charlie’s refrain, “I could tell you some stories,” comes off generous at first, ironic at second, but becomes more and more disturbing each time you watch the movie, knowing as you do the true malice that lives in Charlie’s heart and just how awful the stories he could tell would be.

But no matter: Fink wouldn’t listen, and now the hotel’s on fire and somebody’s head is in a box.

The Big Lebowski: The Eagles. It’s nearly impossible to choose just one moment from The Big Lebowski and put it above the 1001 other moments that make this movie so brilliant. I mean, where does one begin? There’s David Thewlis’ cameo as cackling modern artist Knox Harrington; there’s the scene where the nihilists thrown a marmot into the Dude’s bathtub for reasons passing understanding; there’s the Dude, Walter, and Donny talking about going by the In-N-Out burger after the world premiere of landlord Marty’s dance quintet. And then, of course, there’s John Turturro as Jesus.

But if I had to choose one moment that best encapsulates the brilliance of this movie and which best demonstrates the Coen Brothers’ aesthetic conviction that the line between civility and violence is paper thin and can be crossed at any moment, I’m going to go with the one where the unnamed cab driver throws the Dude out of his cab because he was complaining about his choice in music. It’s an incidental scene, I realize, but the whole movie is incidental (just like its inspiration and blueprint, The Big Sleep), so why not venerate a moment in it that is apropos of nothing?

I’m not sure what’s funnier, that after getting drugged by a pornographer, arrested, and beaten by a Malibu police officer, the Dude cares what’s playing on a cab radio – “Man, come on, I had a rough night, and I hate the fuckin’ Eagles” – or the fact that the cab driver responds to this simple complaint by completely losing his mind, pulling violently off the road, throwing open the back door, and dragging the Dude out of the cab by the scruff of his neck and leaving him by the side of the road.

It’s just a throwaway moment, a touch of nonsense, but the Coens’ worldview may just be boiled down in that small scene: Human beings are never more than an inch away from losing their minds, and there’s nothing you can do about it if they do.

No Country for Old Men: APB. There’s a darkness at the heart of No Country for Old Men that is deeper than anything the Coen Brothers have dealt with before. Everything else they’ve done–even the really bleak stuff like Fargo and The Man Who Wasn’t There–tempers its dread with comedy and cinematic flair. But not No Country for Old Men, which is dismal all the way through. Gone are the wild camera angles and absurdist supporting players, replaced by stark landscapes and a cast of doomed souls dragging themselves toward eternity without salvation. There is no relief here, just the Coen Brothers’ philosophy distilled to its essence: The world is meaningless and cruel, life hangs on by the thinnest of threads, and human desire always leads to unseen consequences of the most violent kind.

But there is one moment that celebrates (quietly and without any real consequence) humanity’s capacity for finding levity in even the worst of all possible worlds. A little gallows humor to get us through the ever-darkening night, a demonstration of the simple truth that the only way to tolerate this broken world of ours is to spit in the face of its seriousness before it swallows us whole. And it will swallow us whole.

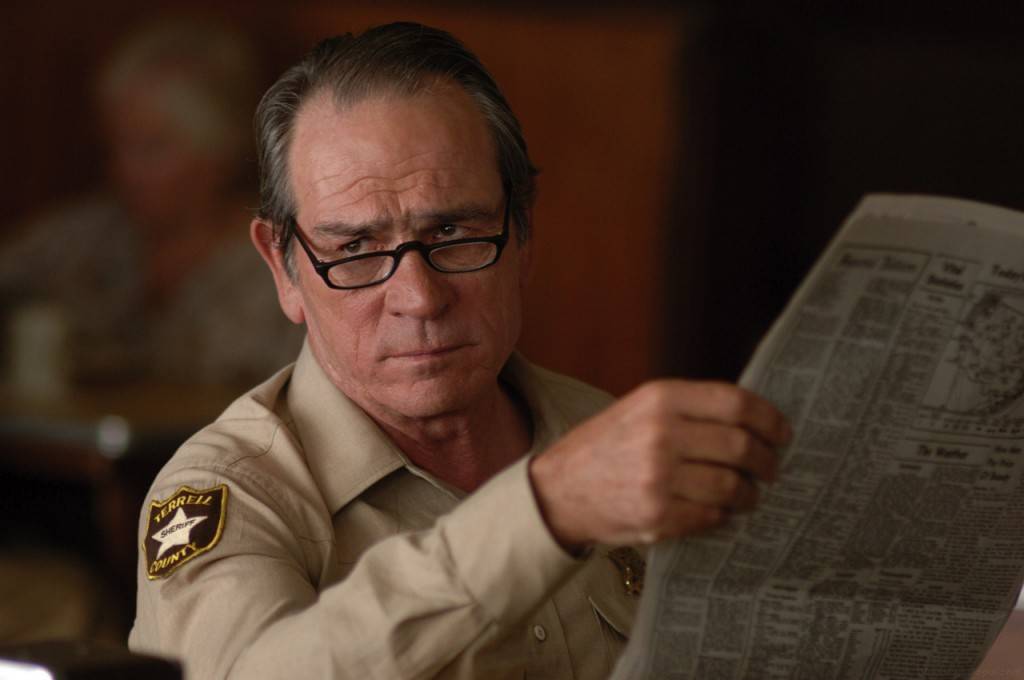

Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones) and Deputy Wendell (Garret Dillahunt) enter the room of hit man Anton Chigurh, looking for the man they believe is responsible for all those corpses rotting in the West Texas desert and who they know is currently hunting down the film’s pseudo-hero Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin). Chigurh is already gone when the policemen arrive, but when they see a bottle of milk sitting on the table with fresh water condensing on its sides, they realize it wasn’t long since the killer was there. The younger fresh-faced Wendell starts to babble excitedly, a kid playing cop: “Oh sir, we just missed him! We gotta circulate this, on radio!” But the older, wiser, and far more cynical Bell is unimpressed. Pouring himself a glass from the “still sweatin’” bottle, he replies, “All right. What do we circulate? ‘Looking for a man who has recently drunk milk?’”

If anything captures better the dark heart of the Coen Brothers 20-year cinematic experiment I don’t know what it is. In their world, we’re all always a split second away from complete catastrophe, and the only ones who are able to maintain any sanity are those who have resigned themselves to the folly of existence and refuse to get excited by false opportunities to rid themselves of life’s burdens.

The wolves are always at the door in Coen land; best to laugh every once in a while to keeping yourself from weeping all the time.

8 responses to “The Coen Brothers’ five greatest moments”