Interview with Collapse director Chris Smith

– by Adrian Mack

So, two movies open in Vancouver. One is so profoundly disturbing and terrifying that a local critic confessed that she, like countless others, was reduced to a “fetal ball”.

And the other one is Antichrist, har har.

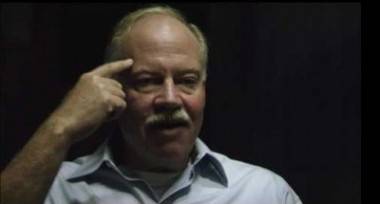

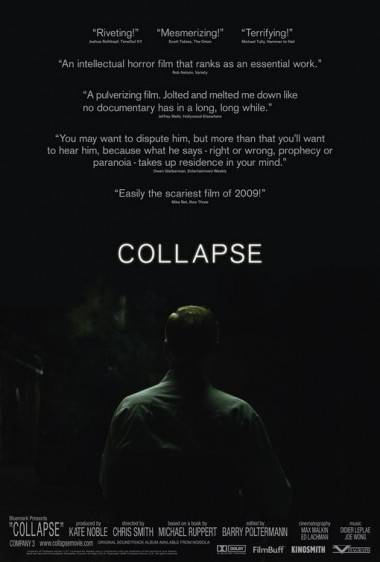

Chris Smith’s Collapse is an elegant 82-minute talking-head interview with investigative journalist Michael Ruppert, in which the former LAPD cop outlines his grand unified theory of the end of civilization. Which, he notes, is happening a lot faster than he predicted. Right now, as a matter of fact.

Ruppert’s predictions happen to carry some weight. In 2002, he began frantically warning his readers of the imminence of last year’s global economic meltdown. Prior to that, Ruppert was digging up cold and hard information about 9/11; information that remains not only unrefuted, but comprehensively ignored.

Before that, as a young cop in the late ‘70s, Ruppert found himself on the CIA’s shitlist when the Company tried to recruit him into its illegal drug-running operations, and he just said “no”.

Watch – Former LA Police Officer Mike Ruppert Confronts CIA Director John Deutch on Drug Trafficking

After dodging a few real-life bullets, Ruppert spent the subsequent 30 years fighting for his professional life and his reputation, suggesting that his enemies shifted their focus to a more lingering sort of assassination.

Now more-or-less retired and poor, Ruppert has the baggy-eyed demeanor of a man giving it one last, emotional shot in Collapse. His argument is that Peak Oil is here – consumption is exceeding production – and our Ponzi-shaped “infinite growth” economic paradigm is terminal. Forced demand reduction will sustain us for so long, until oil prices spike for the last time. In lieu of any feasible energy alternatives, Western economies will fold, governments and infrastructure will collapse, and we’ll be fucked in more ways than you can possibly imagine. Say goodbye to food, to give one example, since agribusiness depends on petroleum not only for transport, but machinery, and fertilizer. Take a look around; it’s already happening.

What makes Collapse so painful is the ironclad logic of Ruppert’s thesis, his fluency, and his evident sincerity. This isn’t the duplicitous libertarian agitprop of a film like Aaron Russo’s From Freedom to Fascism. Ruppert is Joe Friday, not Alex Jones, and his bona fides only appear unlikely on the surface, and depend on your investment in dismissing him. When he darkly informs us that “Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld took great personal interest in me,” one can either view Ruppert as a crackpot, or queasily allow that, yes, Dick Cheney would almost certainly take a personal interest in Ruppert based on the information he published in his 2004 book Crossing the Rubicon.

That Collapse is gaining such mainstream traction is perhaps a tribute to the strength of Ruppert’s analysis, which also forwards plausible reasons for the irrationality of climate change denial, escalating wars, or the continued and illegal embargo placed on the details of Dick Cheney’s fishy energy task force in 2001.

Equally, Collapse is an event that appears finally to be forcing the simmering if unspoken fears of an entire culture into the light of public discourse, while simultaneously pulling back the curtain on our own denial pathologies. Look at this contorted and gaseous essay in the LA Times, in which Ruppert is compared to wealthy corporatist prime-time bullhorn Glenn Beck, both of whom, the blogger desperately and smugly argues, spring from the paranoid impulse of America’s braying, unwashed masses (subtext – “This is the Titanic, you idiots, she’s unsinkable!”).

In an essay on Indiewire, Ruppert is reduced to a curiosity; a standard issue fin-du-monde 2012-era nut, with writer Jeff Reichert preferring to salute director Chris Smith’s radar for “striver(s) and dreamer(s)”. He hopefully calls Ruppert “a Mark Borchardt struggling to make the world into a place where the Yes Men wouldn’t be necessary” (subtext – “I get paid to write flimsy and half-arsed cultural commentary, and by the way I just shat my pants…”).

Filmmaker Smith must find himself in a very odd position, with an unlikely phenomenon on his hands, and a critical community engaged in a fraught attempt to figure out his own editorial position on the material (I think Collapse is nothing if not fair to Ruppert, who, above and beyond his work, might be charitably described as thorny).

The Snipe spoke to Smith from his part-time home in London, England.

Adrian Mack: In your prologue you explain that you approached Ruppert because you were writing a script about CIA drug trafficking. Generally, American movies (not to mention journalists) tend to airbrush federal agencies out of the picture, suggesting that you’re not unsympathetic to Ruppert’s worldview.

Chris Smith: I always look for the human story, and I didn’t know much about the specifics of his case. So it was really just wanting to find out more information, and we were in LA and he was willing to meet up. And when we got there, he just had no interest in talking about it at all. He just asked, you know, did we understand what was happening around us? Did we see the world that he saw? Which we didn’t at the time. Well, I mean, everybody did to some degree, because it was February 2009, and you could tell things were bad. But the layers and the theory he’s come up with, we hadn’t seen it the way he saw it.

AM: It seems people that would have scoffed at Ruppert if they encountered him online are confronted with an inability to argue with his logic in Collapse, and are admitting to having their world shaken by this film.

CS: That’s what interesting, is that I think a lot of people go into it with the perception of wanting to write him off. But then there are certain things he says that strike chords with people that are hard to shake. And I think that’s where it ends up crossing into this space where you can’t quite figure out what to make of everything. Because what he’s saying is actually challenging everything that we’ve taken to be real. It’s hard for people to take. As a side note, I went through all the reviews and cut out adjectives about Michael Ruppert, used just in the reviews of this film, all from people that had seen the same film, and it’s incredible when you actually look at the descriptive terms people have used for him. They’re so across the board. It’s so interesting that one person can elicit such a strong and diverse response from people.

AM: Surprisingly, the NY Times embraced Ruppert as an “authentic human being” and accused the filmmakers of placing him in an “environment that seems custom designed to diminish him…” as “merely an oddball specimen”.

CS: It’s so strange because we spent weeks trying to figure out, “How can we present him in a way that will give him some credibility?” We went to great efforts. I was amazed by the New York Times article because if anything, up until this point, any criticism we’ve had is that we’ve been overly sympathetic in giving a voice to an outsider. It actually completely blindsided us when we spent eight months giving somebody a voice who’s never been acknowledged by any mainstream press in his entire 30-year career.

There’s a section in the movie that pulls quotes about Michael and what people have said about him, and the only article that was ever published that we could find by a legitimate mainstream news source was from 1981 in the LA Herald Examiner about his CIA drug trafficking case. I mean, Democracy Now won’t go near him. It’s as if he didn’t exist, and we spent an incredible amount of energy trying to present him in a way that was fair.

Both American Movie, this movie, and any documentary I’ve made, I’ve shown to the subjects of the film before finishing, and made sure that they felt it was fair. So it’s interesting; it’s a real contempt for the subject of these films because they’re basically saying these people are too ignorant to understand that they’re being made to look foolish.

But in the end, to be honest, I was ecstatic because I would much rather have them praise Michael than me. ‘Cos I don’t care. It doesn’t affect me that much, but in terms of his message getting out and his feeling of vindication after all these years, I was really happy that they were sympathetic to him. Because I think he deserves it. Whether he ends up being proven right or wrong, whether he’s ultimately vindicated or ends up a footnote in history as just another Chicken Little doomsayer, that’s irrelevant. But in terms of this moment right now, I think he feels his life’s work is being acknowledged and taken seriously.

AM: The LA Times was a little more predictable, which is hilarious in view of Ruppert’s on-camera statements about the mainstream media.

CS: The thing that’s interesting about that article is that he [the Times blogger] is putting him on the same level as someone like a Glenn Beck, but Glenn Beck has a national TV show and Michael Ruppert has nothing. I find these disparate stories fascinating, because of the different ways the material is being interpreted or thought about, regardless of whether it’s positive or negative.

I’ve been criticized for not making my viewpoint stronger in the film and I’ve been praised in other articles for not telling the audience what to think. This film more than any other I’ve worked on has had the strangest conflicting reviews that I’ve ever had. Usually there’s some sort of critical consensus, but again, if I go back to this list I made – articulate, wry, pundit of doom, prophet, paranoid, lucid, weary, delusional, sympathetic, lunatic, angry, lonely, vulnerable, poignant, flawed, tragic, crazy, impassioned, nut job, gruff, eloquent, compelling, convincing, disturbing, psychic, isolated, bitter, acerbic, oddly charming, alarmist, visionary, conspiracy theorist, deluded, brilliant, bleak, soothsayer, clever, obsessed, fascinating, charismatic, committed, pessimistic, clear, rational, well-spoken, quack, authoritative, dubious. Those were all the descriptions of him. And that’s all from the mainstream press, all from the exact same film. Some of the contradictory and conflicting ones are from the exact same article.

AM: Over the years, his work and his personality have been blended and muddied. Ruppert has been aggressively criticized for being obnoxious, self-aggrandizing, a demagogue – some of which is true.

CS: A lot of those elements come across in the film. He’s a very complicated person. In one breath he’s incredibly caring and compassionate, and in another breath he’s incredibly bitter and angry; (he) fights to say this is wrong, this isn’t fair, and he’s only gotten criticized, and ostracized, and beaten down for it. But what’s interesting about Michael is that nobody asked him to do this. He took it upon himself. Well, he (also) feels like it wasn’t his choice; that it was brought upon him in being recruited to do something illegal, and that’s what really started it all.

The CIA stuff was definitely something that he felt he wanted to fight to get to the truth. But then from there I think he just never stopped. There was this one clip we didn’t use in the film, so I might be paraphrasing, but he said he just pulled one worm and from there he just kept pulling worms, cause he wanted to find something that he could put his feet on that was solid, that he could stand on and say, ‘This is real”. That’s the quote.

I always remembered it and I always wanted to get it in the film, but we could never quite make it work. It’s really been this 30-year odyssey of trying to get to what he sees as the truth, and at the end of that entire quest was the thesis of this movie and the last book that he wrote (A Presidential Energy Policy). Which is basically that it all comes down to money, and the way that it’s tied into energy, and how it all functions, and how it makes the world go round.

AM: Getting back to his personality, I think some of it comes from what you identify, his frustration and impatience with people not getting it, while his life and career are seemingly being dismantled by an unseen force. But he’s also from a different world; his parents were military and Intelligence professionals, he entered the LAPD in good faith, so maybe part of what we see is a shattered cop who isn’t easy to identify with.

CS: But what makes him equally accessible is that he’s talking about these ideas in language that anyone can understand. He’s also engaging as a person, and you get his life story throughout. So when people say why didn’t you include lots of different points of view, that wasn’t the film that I wanted to make. I didn’t want to make a movie about Peak Oil, or the collapse of industrialized civilization, or the end of the world or anything. To me, Michael was what was fascinating. All those adjectives I gave you before is why. Because he’s all those different things at different times. To this day I find him endlessly compelling. Just the way that his brain works. It’s very different than most of us.

AM: He’s listenable on these topics but he also has authority.

CS: He definitely has authority but he has a sense of humour about it as well. As dark as the humour is, it’s definitely in there. A lot of people that have that understanding and knowledge don’t have the wit that he has, in terms of being able to take the information and talk about it in a way that keeps you engaged.

AM: He’s also been extensively accused of being a provocateur, a double agent, a spook…

CS: I’ve seen everything from CIA, to FBI, to “Israeli disinformation agent”… who knows? He could work for oil companies. I have absolutely no idea.

AM: He’s been accused of that, too.

CS: The thing that’s weird is that you’d expect they would be paying him better. I’ve come to the end of the whole process feeling like I don’t trust anyone or anything. However, when you’re with Michael, there’s something that’s so pure and genuine about how much he actually does appear to care about humanity, about people, and about right and wrong, that I do believe he believes everything he’s saying to be true. However, you don’t know. Once you get into that world, to understand exactly what is real and what isn’t real–you can’t know. We did put that in the film. There’s a thing that says “CIA plant” at one point. We have all these things that he’s been accused of and that’s one of them. We’ve seen everything.

AM: Did you see the story in Monday’s Guardian stating that the U.S. pressured the IEA to fudge decline rates?

CS: I did. It’s funny, we’ve kept up with news stories and information, and that was the first story that really stood out to me. If that’s true, it’s really terrifying because the implications of that lead back to what Michael is talking about in the film, which is not a pretty picture. But until you see the movie, I think most people wouldn’t pay attention to a story like that. My brother is a conservative in Florida who works in real estate, and he’ll send me articles like that now, and so many people who worked on the film, or have seen it, are all of a sudden keying in to things like that where they weren’t before.

AM: I’ve noticed growing mainstream interest in Peak Oil since Collapse.

CS: I think ultimately regardless of what people’s take on Michael is, and I hope people don’t look at him and what he says as gospel, but they look at it as a way to get interested to the point that they want to get further educated by themselves. And as we both know, there’s plenty of scientists, scholars, and economists that fall on both sides of this issue, but I think people would be surprised to see that he’s not alone. His thoughts on these issues come as the results of a lot of other people’s work, and he’s the first person to say that. But I’ve had people that didn’t know anything about Peak Oil see the movie and then go online, and they’re like,”There are a lot of people saying similar things.” But I hope people also don’t categorize it as a Peak Oil documentary, because I don’t think it is. What’s interesting about Michael is the way that he ties everything together.

AM: Crossing the Rubicon basically argues that Peak Oil was the motive for 9/11. Ruppert has distanced himself from “9/11 Truth”, but did it come up?

CS: Neither of us considered it. It wasn’t something that was avoided, so much as it wasn’t the focus of this movie. I felt like that was Crossing the Rubicon and this was about what’s happening now, which in his mind was summarized in the second book. I hope that anyone who’s interested in what he has to say about 9/11 would go and read Crossing the Rubicon because I don’t think many people understand what his arguments were. In that way, I wish we had covered it, because his viewpoints are very different from what people assume them to be. He’s looking for evidence that would be presentable in court.

AM: Ruppert was already marginalized after taking on the CIA, but Crossing the Rubicon pushed him even further out there.

CS: For me the most interesting part of that book is that it’s not been discredited, it’s just been ignored. I don’t know enough about it, and I don’t have the time to dedicate to the research, but I don’t remember seeing any kind of analysis. There’s been criticisms of him…

AM: Ruppert talks about ways to “survive the transition” – have you personally taken any of the advice? Are you peeing in the garden?

CS: I haven’t started peeing in the garden but I did buy some physical gold. And my only regret is that when I first saw him do a lecture, he was talking about buying gold when it was about four or five hundred dollars an ounce. Now it’s eleven hundred. He said don’t get in debt, don’t get caught up in the housing bubble, and buy gold, and of course I didn’t do any of those things then. So it wasn’t until earlier this year that I said, “Alright, well…” I looked at it as hedging my bets. If gold goes down and Ruppert’s wrong, then that’s great. You couldn’t have a better outcome than everything he’s saying not come true. So I looked at it as a hedge.

AM: A win-win?

CS: No, I wouldn’t say it’s a win-win. A win-win is very different, this is a lose-lose.

5 responses to “Collapse director Chris Smith”