Interview – Richard Crouse at the 16th Annual Victoria Film Festival

– by Rachel Fox

Kris Kristofferson was honoured by the Victoria Film Festival this year with the presentation of its inaugural IN award, which celebrates someone “who has been INspirational, INnovative, and INdependant.”

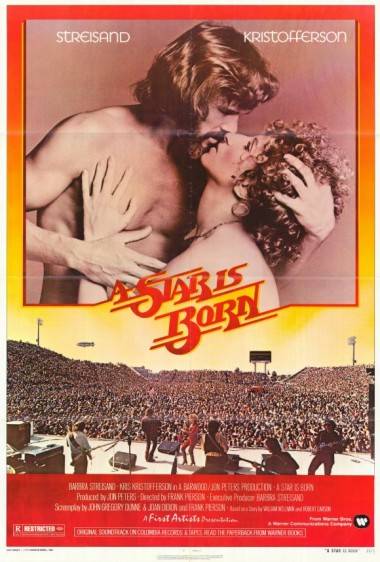

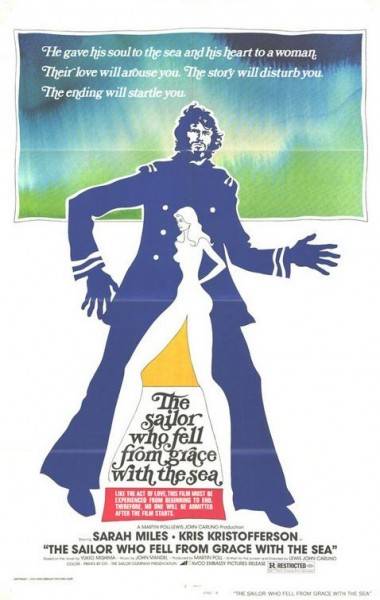

The actor/musician was received warmly by the crowd, which was left utterly charmed by his candor and humility. The former Rhodes Scholar spoke freely and reflected about his incredible life and broad career, from being a janitor at Nashville’s Columbia Records to his emergence as a singer-songwriter associating with the likes of Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis and Janis Joplin before successfully transitioning to an acting career. That includes a memorable stint in a bathtub with Barbra Streisand (in A Star is Born, which earned him a Golden Globe).

A brief question-and-answer period was followed by a rather grainy screening of Kristofferson’s 1996 film Lone Star, which was succinctly summarized by filmmaker Ken Galloway (at the festival with his short film, “Ways on Wheels”) as an example of how “the white man fucks everything and then fucks everything up.” Indeed.

Richard Crouse emceed the evening. I had a chance to catch up with the Canada AM movie critic about interviewing one of his personal heroes, hanging out with Teddy the Toad, and the unexpected treat of falling in love with a woman whose life and story stole everyone’s heart.

Rachel Fox: How’s your experience been at the Victoria Film Festival so far?

Richard Crouse: It’s over, now. I’m done (laughs). It’s been really fun. I cover film festivals all over the world. I go to Cannes, I cover Toronto – I live in Toronto. They’re much different festivals; I’m really working those ones really hard and seeing sometimes 75 movies [at the Toronto International Film Festival] and interviewing people so they’re much different. In this one, I was presenting things the whole time and doing interviews onstage and was more a part of it. So I kind of kicked back and relaxed a little bit at this one …

RF: You kicked back and relaxed in Victoria?

RC: Well a little bit, a little bit. You know what, I had fun here. The people who were here – I got here on Friday and the people that were here were amazing, good fun to hang out with, always something to do. I got to interview Kris Kristofferson tonight which was mind-blowingly cool.

RF: It was sort of like your James Lipton moment.

RC: I do a lot of these kinds of things in Toronto and other places too, but to sit next to him, that close… I don’t know if you could tell from the audience, but he teared up when he talked about Janis Joplin. That was… those kind of moments that I didn’t expect, and as an interviewer are very special and as an audience member I hope so too.

RF: What I noticed during the interview was he had this way, a sort of humility about him – he almost was like a little boy. He’d be talking about something and then he’d laugh about it as though it was no big thing. I thought it was quite endearing.

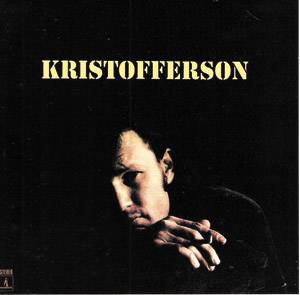

RC: Considering who he is, and the songs that he’s written – if he had only written “Me and Bobby McGee”, that would’ve been enough. If he’d have only written “Me and Bobby McGee” and “Help Me Make it Through the Night”, that would’ve been enough. If he had only written those and “Sunday Morning Coming Down”, that would’ve been enough.

But the film work on top of that – for 40 years he’s been making records consistently, and good ones, and films, and working with directors like Martin Scorsese and everybody else. It’s kind of one of those unparalleled careers in terms of a musician who has branched off and done other things, considering the amount of success he’s had. I’m thrilled to sit and do it.

The cover of Kris Kristofferson’s first album (1970), which introduced “Me and Bobby McGee” to the world.

RF: Looking at someone like Kris Kristofferson and the career transitions he’s made – it’s something we’re seeing a lot more of now; artists who start as musicians and then suddenly they become actors and then perfumers.

RC: We’re only seconds away from Lady Gaga making a movie and having a clothing line. I think though, in some ways, it happens so quickly now that it dilutes the brand, and none of it is done particularly well. Whereas maybe I would’ve said that about Kris Kristofferson in 1971, “He’s a songwriter, what’s he doing making movies?” But he stayed at it and worked at it for so long and really made it not just a sideline, but a really parallel career. That’s interesting to me.

RF: One thing that you touched upon in your introduction of him was that “independent spirit”, which you spoke of along with the likes of Johnny Cash. When I think of Kris Kristofferson, one thing that always comes to mind is (I don’t recall what the event was) was when Sinead O’Connor performed for the first time …

RC: I was there.

RF: Were you there?

RC: I was. It was at Madison Square Gardens. She had torn up the picture of the Pope on Saturday Night Live the previous Saturday. I’d forgotten about this, or I would’ve asked him about it.

RF: Ahhh!

RC: See, I should’ve talked to you beforehand. [Laughs] It was at MSG, it was the 30th anniversary of Bob Dylan on Columbia Records. There was, I don’t know, 40 bands or acts – everyone from Eric Clapton to Sinead O’Connor. And so she comes out, and it’s horrific-

RF: I remember watching it on television and just being stunned at the [audience] response.

RC: Sitting in the audience watching that, I felt like, “Great violence could happen any time now.” It was one of those times that the feeling changed in the room so quickly, and there’s 50,000 people –

RF: New Yawkers…

RC: New Yorkers, who were angry at her. And Kristofferson came out because he had hosted part of the evening. He put his arm around her and said, “Don’t let the bastards get you down.” And I remember it being such a cool moment, because it’s not like he took her off stage and did it. He did it onstage, and said to the audience, “I know what you’re doing, and I’m gonna help her.” And then Neil Young came out and blew everybody’s mind playing “All Along the Watchtower” and lifted the crowd right back up again. But it was Kristofferson’s moment.

RF: I remember that. When I think of him, that’s what comes to mind.

RC: I think that’s kind of emblematic of how he is. It seems to me that he, even if it’s not going to be popular, he does the right thing. Because he was then staring down 50,000 angry people –

RF: New Yawkers…

RC: – who were not really happy at him. It’s kind of a cool thing.

RF: You spoke a lot about the musical portion of his career and how that’s influenced you. What was preparing for this interview like? You seem to be a fan.

RC: I am a fan. I’m a pop-culture junkie. I had to do research for this, a great amount of research, because I wanted that no matter where the interview went I was going to be able to go there. I don’t like to plan my interviews particularly well. I don’t like to have a list of ten questions. I didn’t have anything written down. I had a couple of quotes written down that I wanted to ask him about just in case I got stuck but there were no actual questions written down.

“Me and Bobby McGee” was a really significant song for me, I loved it. I was too young – even though I’m Toronto’s oldest living man – I was still too young for the original Janis Joplin version which wasn’t really significant to me when it came out. It became really significant to me years later – the song, it tells a story, the vocals are amazing. There’s so much to it, and he wrote it. I wanted to be clear that it wasn’t one aspect of his career that had blown my mind. There were a number of things there that I’m really impressed by.

RF: He speaks to another era, of film makers and songwriters, who tell a story.

RC: The storytellers. I’m not sure that it would be such a bad thing if there were more people like him, working in both film and writing songs.

RF: Any other parting words about your experience here in Victoria?

RC: It’s been fun, you know. I got to hang out with Charles Martin Smith, which was totally fun. We ended up hanging out for three solid days, pretty much. It was hilarious.

RF: I spoke with him a little bit. He called me “schmoozy”, or rather, “charming”.

RC: [Laughs]

RF: I reminded him of a time – true story – he almost hit me, or rather, more likely I almost ran into his car on my bike…

RC: Terry the Toad almost hit you! That’s cool, though.

RF: It was really exciting. I wasn’t wearing a helmet …

RC: See, you should be wearing a helmet.

RF: I do now.

RC: I’m old, and I’m telling you that. I must sound like your father. Anyways, I think the festival is attracting a really interesting crowd this year. I haven’t been before, but Charlie was a lot of fun to hang out with. I hosted two days of SpringBoard Talks as well, and Academy-Award-winning director Chris Landreth [Ryan, 2004] – his talk was unbelievable. It made me understand, finally, why I hate Robert Zemeckis’ stop-motion movies. I’ve always known why, in my heart…

RF: Why?

RC: Because they look dead in the eyes. And he explained to me why they look dead in the eyes. It was fascinating.

RF: I wish I’d seen it.

RC: Of the SpringBoard Talks, although many of them were really fascinating, there was a woman named Madeleine Sherwood, and I just fell in love with her.

RF: I heard the crowd was left “misty”.

RC: Oh my God. She was the final speaker of two days, and it was pretty much the same people who came back and saw both things. And they were long sessions, they were three or four hours long with no break. I was literally just like, “Next! Next!”, bringing them all up on stage, one after the others. Some speakers were great at engaging, others maybe not as much, so it was a mixed bag.

And then we bring her up after showing a short film about her life, about how she was sent to a mental institution and escaped, and thought, “where should I go?” And she goes to New York to become an actor, it was far enough away that she figured she’d be left alone and ended up originating 18 Broadway shows onstage, including Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and The Crucible. Unbelievable stuff. And then she comes up and she’s endearing and amazing and knew Elia Kazan and told stories about Marilyn Monroe… It wasn’t just the stories, it was just her. She was really kind of incredible.

RF: A textured life?

RC: More than just a textured life. She is a woman who really bucked trends her entire life. She comes from a well-to-do family in Montreal, escapes from an insane asylum, becomes a Broadway star, marches with Martin Luther King in the South and gets herself arrested, and instead of doing what everybody else did – which was get the hell out of there, or hire some hot-shot white lawyer – she hires the only African-American lawyer in Alabama to represent her, which was probably, at the time, going to guarantee her to lose. But she believed in it, and she had the strength of her convictions. I was amazed by her. She was lovely, and of all the people that I’ve met here – she was the treat, the unexpected treat.