Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller, and the beginning of the B.C. film industry

– by Regan Payne

A strong case could be made that Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller launched the Vancouver film industry we know today.

A quick look over local film industry lists of the last several years shows no end of well-known features that have been committed to print on these ebullient shores. But, unless you’re a fan of superheroes with titanium claws and big sideburns, the search for classics is akin to the quest for the much promised, low-income housing among the newly constructed Olympic Village: simply not present, no matter how hard one squints.

With a track record of sometimes expensive, often forgettable fare, the Vancouver film industry gives the impression of having been established by directors of the fading Italian schlock horror genre, or Russ Meyer, arm in arm with a bevy of buxom blondes, ready for their, ahem, close-up. However, 40 years ago, two features were shot in Vancouver within striking distance of one another; both are now considered classics of the resurgent American independent cinema movement of the 1970s. And Vancity is showcasing one of them this weekend.

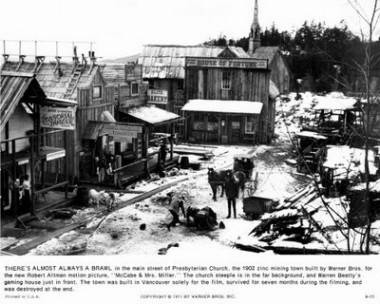

In 1971, Comedian turned filmmaker Mike Nichols (The Graduate, Working Girl, Closer) was busy shooting scenes with Jack Nicholson, Art Garfunkel, and Candice Bergen at what was then known as Folkestone Studios in West Vancouver for his much ballyhooed Carnal Knowledge. A stone’s throw away, Robert Altman and his personnel were busy constructing Presbyterian Church, an actual Old West mining town for his period Western, McCabe & Mrs. Miller. (Vancity Theatre is screening the film Jan 28 – 30 and Feb 2 – 3; see their site for details.)

With Altman’s death in 2006, the great director’s career has been the subject of much conjecture and analysis, and with each passing year more and more cinema historians, collaborators, and film buffs are ranking McCabe as his very best. This from the man who helmed the original MASH, Nashville, The Player, Short Cuts and Gosford Park, to name a few. René Auberjonois, who was the original Father Mulcahy in MASH, and collaborated with Altman on many of his early pictures including McCabe, told me over Skype one recent morning that in a career spanning five decades and counting, McCabe is the best film he’s ever been in. “That is the one that will be on my tombstone,” he chuckled.

British Columbia-born producer James Margellos, who also worked with Altman on many of his early films, including McCabe, was instrumental in helping the director initially discovering Vancouver’s exterior, as well as interior, beauty for an earlier Altman picture.

Margellos had bounced around L.A. and Toronto, working as location manager and production manager on a couple of movies. “When I returned to LA, I met an assistant editor that wanted to direct and he had a fairly decent screenplay, and his friend, a stuntman, was going to star in it. He also had a person with some money that wanted to get involved. We were all very naive. The money person said that the first thing we needed to do was get an office.”

The film industry is littered with stories beginning in a similar vein. Soon, the backer backed out, and Margellos, as “producer”, was left to tell their landlord they would not be able to pay their rent, now or ever. The landlord in question, a certain Mr. Aldrich, like everyone in LA, was also in the film business. After some initial awkwardness, the two began chatting about their chosen profession, and Aldrich told Margellos he had a picture that was to film in London, and he was not looking forward to the travel, nor working that far from home.

Margellos asked what the film required. “A place that rains a lot,” his landlord replied. After a quick description of his hometown, the two parted.

A few days later, Margellos received an 8 a.m. wake up call. “My landlord was on the line and he said he was calling from Vancouver and said it was perfect for his project and asked me what I did, I told him I was a production manager. He asked me to call his partner right away and get a plane ticket to Vancouver and get there that same day. That was the first time I knew that our former landlord’s name was Robert Altman, not Aldrich. That picture was That Cold Day in the Park [the film Altman made before MASH].”

By the time McCabe rolled into production, two years later, MASH had made Altman a star, and he returned to Vancouver with his core team to create a Western like no other in film history. “Bob loved Vancouver,” Auberjonois told me. In fact, Auberjonois recalled Tommy Thompson, Altman’s longtime producing partner, telling him back then, “The only problem with making in a film in Vancouver, is there’s no one to bribe.” The implication being that movie productions often find themselves needing to grease some palms to meet their filming requirements, and Vancouver’s film landscape circa 1970 was virtually palm-less, so to speak.

Among Altman’s core team was cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond, who thinks back of McCabe in these terms: “Even after all these years, I was never in a more wonderful, beautiful environment than in that movie.” Not exactly faint praise when one considers that Zsigmond won the Academy Award for Best Cinematography for his work on Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, as well as filling his dossier with such cinematic achievements as Deliverance, The Deer Hunter, and The Black Dahlia. His latest effort to be released was Woody Allen’s 2010 movie You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger.

When he spoke from his home in Los Angeles, Zsigmond reminisced fondly about the few months he spent filming in Vancouver, recalling wistfully the view from his rented apartment overlooking Horseshoe Bay, where he’d watch the ferries come and go over morning coffee. The discussion that followed was practically a dissertation on creating a cinematic classic, from a master of his craft. And like all art that is considered historically valuable, the story of how it became so follows no pattern that can be bottled, copyrighted and sent to the factory floor for mass assembly.

“Every day was a challenge, because sometimes you didn’t know what you would be shooting the next day,” Zsigmond says. Altman was famous for his liberal use of the script he had commissioned. So much so that Ring Lardner, who wrote and subsequently won the Oscar for his screenplay for MASH, apparently viewed his lack of recognizing Altman’s work and re-drafting of his script as his biggest professional regret.

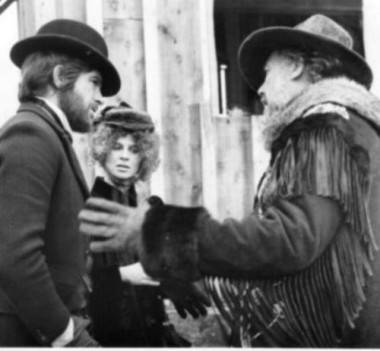

Zsigmond’s recount of McCabe appears typical of the Altman experience. “The day that we started the movie and got the script, that was not the movie we ended up with. They were writing every night: he, and Warren Beatty, and Julie Christie. They were writing every night to make things better.”

This methodology of unencumbered artistic freedom bled into all areas of production. The actors were encouraged to build, and live in the shacks, huts and temporary domiciles their characters occupied. Don Carmody, now a producer of such films as Chicago, as well as last year’s Genie winner for Best Picture (Canada’s top film prize), Polytechnique, earned his first film credit on McCabe as an unpaid production assistant, often driving Julie Christie around the city while attending film school. “It was my very first on-set experience. I didn’t know what to expect. At first I thought it was very professional, but years later came to realize that it was sort of anything but. Pretty standard for Altman though, I gather.”

That “Altman standard” was critical in the very subjective debate of what makes cinema art. Auberjonois recalled Altman often saying, “Most of what I do fails, that’s what makes it art.” Beyond this, however, Vancouver, at that time, provided Altman the distance he required from the studio to make the most of the opportunity in front of him. Carmody confirmed, “Because of union rules, at first we weren’t permitted to do a whole lot on set. But eventually, because of where we were shooting, a lot of crew looked the other way. And Altman wanted us to do things so he could put more money on the screen.”

And so he did. McCabe looks like no other Western before or since, which was the result of what is known as flashing the film, a process of underexposing the negative to create a grainier look, considered so dangerous that no Hollywood studio would agree to be an accomplice. This look however began much earlier, as a result of Vancouver’s monotonous cloudy skies.

“He wanted to make this movie like an old Western,” cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond told me. “And Vancouver is always overcast, and it created this kind of feeling that was different. We loved that. In those traditional Westerns, the sun is always shining, and everything is beautiful – it was almost the opposite to that.”

However enough clouds stacked on top of one another can have an overly dramatic effect. “Sometimes it was so dark in the morning, even 10 o’clock, my light meter didn’t even show that light was coming from the sky. And I waited and waited, and told Robert, ‘We have to wait because there’s not any exposure.’ Finally, he who is so patient, said, ‘I don’t think we can wait any longer, why don’t we just shoot this. We’ll see the dailies tomorrow, and if you don’t like it, we’ll do it again.’ When we saw it the next day, he was surprised that we got this incredible kind of quality, because of the underexposure. It was grainy, it looked like old photographs from 1800 and something. We loved it, and thought maybe we should continue doing this, because whatever we are doing is right.”

There was still the problem of finding a lab to flash the film to Altman and Zsigmond’s specifications. “There was no laboratory willing to do it, because it was dangerous to pre-expose the film. It was unheard of. Altman wanted to use the Vancouver lab. There was only one at that time, but it was a 16mm lab, and we were shooting on 35mm anamorphic. So he talked the laboratory into buying the 35mm equipment by paying the bill upfront.”

Zsigmond continued, “Then we could do whatever we wanted. Altman picked the percentage of flashing that he wanted and the lab did a great job. There were a couple of real geniuses there. I cannot imagine that we could have done a better job in Hollywood.”

Which is much to the point – many of those now iconic films of the 1970s, while distributed and owned by the major film studios, were being shot away from the traditional Hollywood setting, providing the filmmakers far more opportunity to stretch their artistic muscle. The movement coincided with the persistence of filmmakers and their collaborators to push more and more realism onto movie screens.

For decades, the Hollywood studios had come as close to perfecting a moviemaking formula as there has ever been. The back lots housed the world, literally. Cinematic landmarks were targeted not by authenticity, but rather by a director’s technological inventiveness, such as Orson Welles’ and his cinematographer Gregg Toland’s use of deep focus, or through understanding and subtly playing a script’s subtext. Studios were either slow on the uptake or underestimated the influence of filmmakers such as Welles, Nicholas Ray and Douglas Sirk, or Europeans such as Jean-Pierre Melville: directors to whom the rigidity of traditional studio filmmaking was becoming increasingly absurd as the stories they wanted to tell required more and more reality.

Marlon Brando’s far more realistic approach to acting was also influencing a generation of actors, some of whom would find their way into the director’s chair by the late sixties, and become leaders of this new movement of independent cinema, such as John Cassavetes, and the recently departed Dennis Hopper.

Both Nichols’ and Altman’s films broke new territory (Art Garfunkel was the first person to show a condom on film in Carnal Knowledge), and it is debatable whether they would be the films they were had they not been filmed in Vancouver. Zsigmond doesn’t believe so. “We could not have done it in Hollywood. We were just lucky we were at the right place at the right time, with the right weather. Everything was just working for us.”

Zsigmond has only returned to Vancouver for work one other time in his career, during the mid-90s for the Richard Gere-Sharon Stone marital drama, Intersection. By that time, Vancouver had a similar industry infrastructure to LA, New York, or Toronto, and the changes were obvious. “We used a lot of local members on that film. I only probably brought my gaffer (head electrician) with me because I always like to do that. But all the other crew members were from Vancouver. It was a much bigger industry, everything went almost like it would in Hollywood.”

Vancouver, and its film industry and capacity, is much changed now, and Auberjonois speculated as we spoke, “Someone like Bob Altman [were he still alive] probably wouldn’t want to work in Vancouver anymore.” And therein lies the real tragedy, and perhaps the answer: if McCabe & Mrs. Miller were to be made today, it wouldn’t be made in Vancouver. An artist such as Altman or those like him, the ones we crave to create lasting, memorable images from a city like Vancouver, would seek out a fresh landscape, untouched by the Hollywood machine, upon which to create their masterworks.