VIFF reviews – Michael, This is Not a Film and Martha Marcy May Marlene

– by Julia Brown

The Vancouver International Film Festival may have wrapped up for another year, but that doesn’t mean many of the entries aren’t still worth talking about. The Snipe film reviewer Julia Brown checks in with three more capsule reviews from this year’s fest.

Michael (Austrian, 2011) – Michael (played by Michael Fuith) is presented as a pretty ordinary guy. He has a job in the insurance business (he even gets a promotion at one point), a mother and sister who seem to care about him, and even a few casual friends. Yes, he’s a bit on the quiet side, but from an outsider’s perspective his deviance is far from obvious. The audience, however, is privy to the creepy dynamic he has with his child captive (played by David Raunchenberger). Thankfully, no direct abuse is shown, but the implications of the abuse are somehow worse. Indeed, throughout the film Austrian director Markus Schleinzer, a casting director for filmmaker Michael Haneke, explores the idea that not-knowing can be worse than knowing the full horror. And, in Michael, Schleinzer – who also wrote the screenplay – avoids taking a hysterical or overly-moralistic approach, which adds to the film’s credibility. Overall, though, the movie does not have enough substance to elevate it beyond its discomfiting subject matter.

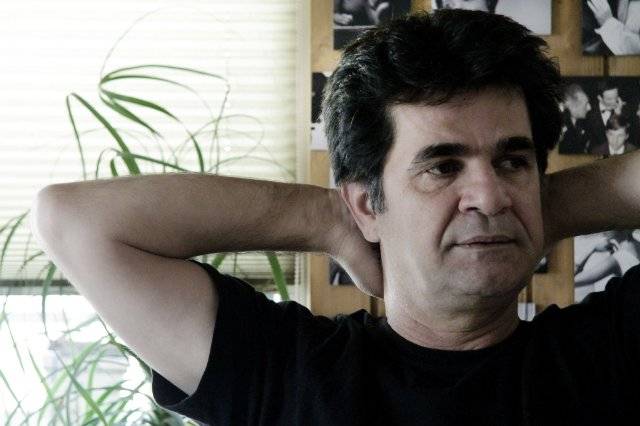

This is Not a Film (Iran, 2011) – Facing a 20 year ban from directing, writing and/or producing films and up to six years in prison, Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi enlists the assistance of friend and documentarian Mojtaba Mirtahmasb to come over to his house and basically turn on a camera. His reasoning being that, although he is forbidden from writing and directing, the ban did not technically mention anything about describing and acting out the film he had in the works but was ultimately prohibited from making. Of course, it doesn’t take long for Panahi to come to the conclusion that “if you could just tell a film, you wouldn’t need to make films.” Frustrated with not being able to communicate his vision in a full visual sense, Panahi’s non-film then become something between an amusing slice-of-life piece and a powerful political and artistic statement. Panahi’s obvious passion for filmmaking and his steely determination to tell his own story, and by extension the story of all artists who are silenced and oppressed, can’t help but inspire admiration and respect. This is Not a Film may not be a traditional movie in most respects – part of it is filmed on an iPhone camera – but it carries an important message about freedom of artistic expression, and therefore is a must-see for anyone who loves film.

Martha Marcy May Marlene (USA, 2011) – The power of Sean Durkin‘s Martha Marcy May Marlene, about a former cult member, is largely due to the performances of the actors, Elizabeth Olsen (as Martha/Marcy May) in particular. Much has been made of the fact that she is the “other Olsen sister”, and likely some of the buzz around this movie is as a result of her familial connections. But Olsen also gives an amazing performance in this film by managing to capture the conflicting emotions and direction-less feeling that all members of cults (or cult-like groups/relationships) must feel if they leave that sort of extremely controlling environment. In fact, Martha doesn’t even seem to have the words to describe her experience. And one point, she asks her sister Lucy (Sarah Paulson) if she is “ever unsure if something is a memory or just a dream.” It is as if Martha is trying to wake up, but her mind keeps pulling her back into the dream-like and/or nightmarish world of the cult, particularly back to her memories of the creepy yet charismatic (but not in a clichéd way) cult leader, Patrick (played by the excellent John Hawks). Durkin, who also wrote the screenplay, stays away from portraying Martha simply as an innocent victim of an evil cult leader – she is both victim and a willing participant. She may be brainwashed, but Durkin seems to be implying that we’re all “brainwashed” to an extent regarding what constitutes “normal” behaviour. The ending is ambiguous, which is in line with the general tone of the film. And it is this ambiguity that sticks with you and raises questions in your own mind that are tricky to resolve. Overall, it is worth viewing for Olsen’s performance and for the haunting quality of Durkin’s filmmaking.