Interview – Will Sheff of Okkervil River

On Oct 27, we lost one of the most influential musicians of our time – Lou Reed, responsible for pioneering a gritty, poetic punk sound in New York in the 1970s. A treasured friend to an honoured and lucky few, and a hero to many more, his immense contributions as an artist, a band-mate, a mentor will never be forgotten.

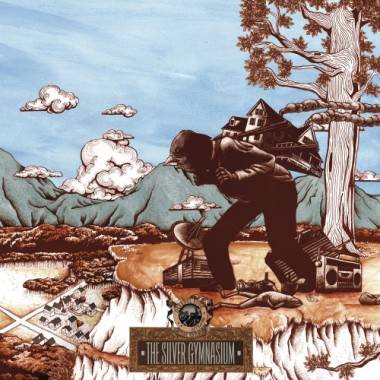

I spoke with Will Sheff of Austin band Okkervil River the day before Reed passed – a day later, he penned one of the most beautiful and moving obituaries for his personal idol that has been published. The honest and relatable prose he invokes in his tribute is one of the defining and shining features in his songwriting, particularly in the band’s latest record The Silver Gymnasium.

At the time, our conversation revolved around more of Sheff’s literary and musical influences. Whether it was James Joyce, Henry Miller or a long lost letter he received from one of the founders of the Incredible String Band, his eclectic range of heroes have informed Okkervil River’s rustic, poetic and intelligent artistic direction. Below is a transcript of our very in-depth, often hilarious and overall enlightening conversation.

Ria Nevada: The new record has a nostalgic, pensive vibe to it, particularly tracks like “Pink Slips” and “It was my Season” – really heartbreaking stuff. Were there specific life events that inspired these songs?

Will Sheff: Yeah, there’s a lot of sort of autobiographical stuff in “Pink Slips”. Actually, that was near the end of the writing session. I decided that I needed a couple more songs and a friend of mine has a little house that she bought in upstate New York. So I went up there to do some writing and brought a ton of magic mushrooms and just stayed in their little cabin. And there was a snowstorm and my car died and I got stuck up there. And I had to get a jump while I was totally tripping, and it was from this weird guy who lived down the street. And the whole time I was writing “Pink Slips” – I’d take a break, I’d write a verse, I’d take a break, I’d write another verse. And it was kind of like a personal anthem and a taking stock of where I’m at and who I am and what it is that I do.

A lot of this stuff is very autobiographical. It wasn’t necessarily written with the goal of making people wonder what these songs are about or even elucidating real things that happened to me. It was more that I wanted to talk about memory and childhood and nostalgia, and I don’t think it’s possible to talk – or it’s certainly possible, but it’s probably not advisable to talk about those things in a general sense. I think it’s best to put something real on the table because people are gonna respond to that realness, and they’re gonna respond to the actual personality and passion, and that’s the real goal – to try to get people to think about their own reasons for nostalgia or their own childhood memories by offering up some of mine.

RN: Vivid, poetic lyrics are a defining feature of your songs – Is it true that your band name is a nod to Russian literature?

WS: Yeah, although, you know, yes it is. It’s not necessarily – when you’re trying to name a band it’s a really difficult thing. You feel like some really super personal and almost like childlike part of your brain is being exposed for the other people in the band. And everybody tosses out names and you’re like – they all sound so terrible.

RN: Veto.

WS: Yeah, yeah! It would be like “What about the Raptors!” (laughs) Something terrible, and then everyone’s like “Oh my god. Really dude?! Really? That’s what you really want?”

RN: That person’s like, “I’ve been thinking about this since I was three years old.”

WS: Yeah, and so you’re just throwing out anything that occurs to you. And I had just recently read this short story “Okkervil River” by this writer Tatyana Tolstaya and I just really liked it. And I threw it out as a name and it was like one of the few names that nobody in the band seemed to totally hate. And they rallied behind it, though I wasn’t sure that I actually liked it, and immediately afterwards, like a couple days later I was like “I’ve been thinking about it a lot and we really have to change the name of this band.” And I just realized it a couple of days later because we had already made a demo – and there were only twenty copies of the demo and the artwork was done at Kinko’s.

RN: God bless Kinko’s.

WS: Yeah I used to know my way around a fucking Kinko’s, I’ll tell you that much! Like making posters and all that crazy stuff. I got real inventive with Kinko’s. My mother, because my parents were teachers, I used to tag along with them on academic errands.

RN: My mom’s a teacher too! And she loves Teacher Heaven in Austin.

WS: Oh I haven’t been there because I haven’t had a reason to, but at boarding school, or any school, she’d often have to make photocopies. So I would go to the copy room and copy parts of my favourite books and play with the big paper cutter. So now the smell of fresh photocopies and all that – so when I was in Kinko’s I was kind of in heaven. Every time I go into an Office Depot or whatever, I get really giddy and I’m like “Oh my god I can buy this hole puncher!”

RN: I’m interested to know what essential reads are on your shelves.

WS: As far as essential, that’s just tough because I don’t – I’m specifically me and I don’t want everybody to necessarily be me. So I’m not gonna tell them the exact books. I remember when I was growing up, and I think in a lot of ways this informed who I am for better or for worse, but I had this sort of mentor, a teacher at school who was English, and he was very, he was real cool, he was some new guy, real great dresser, he chain-smoked these cigarettes he’d roll himself – in fact he ended dying of lung cancer really young. And he took me seriously as an artist. I admired him, and he repaid that with respect. And I would go to his apartment and he would give me books to read. He would say, I don’t remember how this all started, but like I guess I was into Dylan Thomas and so he would be like “You haven’t read Under Milk Wood? You know, you should read that.”

And then I would read all this Dylan Thomas stuff, and then he was like, now you should read James Joyce, and I was reading Proust, and he had me reading the big white male, European novelists of the early part of the 20th century – like all the big literature tomes. And that’s why I use words like “tomes” now. (laughs) I really do still have a soft spot for like the big modernist stuff.

I went away to college and I was writing really Joyce stream-of-consciousness style stuff, or like sort of Faulkner, very intricate sentences, and they hated it. They hated it, they hated me, everyone was trying to write these hard-boiled – all the guys were trying to write hard-boiled Charles Bukowski kind of stuff, and all the girls were trying to be like confessional Anne Sexton kind of writers. And I was using these like ten-dollar words and being very sort of stream of consciousness and showy with my writing. So that’s the stuff that I came up with I guess.

Also a writer that I never outgrew, who’s like the rich man’s Bukowski, as opposed to a poor man’s, is Henry Miller. And I really love Henry Miller, and I keep waiting to get embarrassed by it or grow out of it. But every time I pick up a Henry Miller book again I’m like “Yeah! Yeah! I love this guy!” I like his attitude. But that’s the stuff that I sort of came out of. And I think also, reading all those books, especially Joyce, Faulkner and Proust, and Dylan Thomas, there was a real effort on their parts to capture communities. So I think that was kind of in a way inspirational for The Silver Gymnasium.

RN: Do you have a narrative structure in mind when you’re writing songs?

WS: Not necessarily. I often get annoyed with songs like that – Â “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” is the first thing that pops into my mind (laughs). Like any song where they’re telling a story, and this happened, and then this happened, and the devil said this, and then he pulled this out. Those songs bum the shit out of me. They bother me. So, what’s often happening is that I have a character in mind and the character is getting the chance to tell their story.

Although with this, I started to break away from that a little with I Am Very Far (2011)Â because I felt like I had done that a lot, and I started trying to write more poetic and abstract and kind of where it was hard to understand what exactly the narrative was.

With this one, I think in a lot of ways that was a beginning of a new style of writing for me. I tried to write in that same sort of, not character-based and not linear way but more about my own feelings. I always like when a song feels like a big outpouring of – like where somebody just cornered you in a bar and they’re talking to you and you’re drunk too so you’re trying to remember what they said and piece together a story.

RN: So you find that you were a little more vulnerable maybe writing this record?

WS: For sure. And it’s not just that. I wanted to just be straight with people. I want to look people in the eye and say this is what happened to me, this is how I feel, I’m not gonna bullshit you about anything. I’m just gonna be real. You know? That was sort of the strategy behind the way the voice worked.

RN: When we saw you last here, you were on tour with Titus Andronicus. They did this nifty little thing when they were promoting their last record Local Business where they did a series of short performances in their favourite local spots. You guys are from Austin, where practically every café, BBQ joint and food truck doubles as a venue. But what’s the most unconventional place in the city you’ve ever performed in?

WS: In Austin or ever?

RN: Ever.

WS: One time, I can’t even remember them all, but this is a funny one. We had these kids, gosh I don’t know what happened to them, they’re probably all old in an old folks’ home now (laughs). We had these kids in Omaha who were our earliest, obsessive super fans. They were really young – they were all in high school I think, maybe freshmen in college, some of them.

And they were obsessed with us, they were so sweet, and we were passing along through some place and they really wanted us to play Omaha so they set up a show for us and it was a show at a placed called California Taco? I think? A local Omaha place – and we showed up there and they booked it, and the opener was this kind of dorky kid who was wearing this blazer, really sweet kid. He had a little classical group, they opened for us, all high school kids, and the audience was all parents and really nice high school kids.

And after the show, we went downstairs, somebody worked there – it was one of those places where it was suspicious how his staff was all kind of hot young girls. And I guess it was some bachelor dude who owned the place and afterwards we went down to the basement I think to smoke pot and it was the guy’s bachelor lair and he had a waterbed and it was obviously where he’d take the girls, really super sleazy down there, like a love den you know?

RN: Oh no! So this was underneath California Taco?!

WS: It was underneath California Taco. And then afterwards we went back and one of the girls’ parents picked us up – we were allowed to stay there. And the girl was like, “Oh my parents will be fine! They’ll make you breakfast in the morning and it’ll be great.” So we went back and stayed up and talked with them for a little bit and in the next room the dad was sitting there really tense, like pretending to read a book but like he didn’t trust us at all. You could tell.

And in the morning, they all had to go off to school and they were talking about how the parents were gonna make us breakfast, and basically as soon as they were out of the house, the parents were like “You got what you need? Can you go now?” They were like, these guys are gonna try to sleep with them, they’re a bad influence or something.

RN: I can just see these kids cracking open their piggy banks like “We’re gonna get Okkervil River!”

WS: That’s what it was like! They were sweet kids. I wish that the dad – and if I was the dad, I would have been the exact same guy – but I wish he could have known that our intentions were pure! (laughs)

RN: So this leads to my last question – as a teenager, who would you have cracked open your piggy bank for?

WS: Well this is a really weird, specific thing for me. I was a little obsessed with a band called The Incredible String Band when I was in high school. They’re kind of the first psychedelic folk band? Back in the ’60s, they were the first band to just do this psyche thing that was all rooted around acoustic instruments, and rooted around sort of international music traditions, you know, and blending them and fusing like Indian classical music with Scottish folk songs and stuff.

And they had these like 15-minute songs that were suites that had all these different parts – I remember, the guy is still around, and he became a harp player. I wrote him, I was obsessed with that band, and I asked him for advice as a songwriter. He got back to me something like two years later – I had given up, I was like, whatever, I’m never gonna hear back from this guy. I would kill to find this note, I know I have it somewhere.

He wrote back to me, just write about what you feel, write really honestly about what’s meaningful to you, and don’t try to write in any style, just be yourself. And that was his advice. But it was so nice of him that he wrote back to me!

RN: A story to warm our hearts.

WS: That’s right.

2 responses to “Okkervil River’s Will Sheff (interview)”